Saturday, March 01, 2008

Friday, February 08, 2008

Monday, October 24, 2005

Saturday, October 22, 2005

The Nature of Maps

“Nothing is definable, unless it has no history.” — Nietzsche

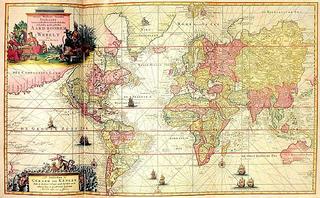

I love maps. I am interested in them because they embody many of the things I like. Maps are cultural artifacts comparable to diaries, art objects, literature, or musical instruments. Almost every culture had developed maps, but they did it with enormously varying degrees of sophistication. The origin of maps seems instinctive, in that they are products both of the intellect and the imagination confronting problems in reality. That is, in the quest to describe reality, maps tell stories. They help construct a history in which they are a part. I like all of these things, especially stories.

I love maps. I am interested in them because they embody many of the things I like. Maps are cultural artifacts comparable to diaries, art objects, literature, or musical instruments. Almost every culture had developed maps, but they did it with enormously varying degrees of sophistication. The origin of maps seems instinctive, in that they are products both of the intellect and the imagination confronting problems in reality. That is, in the quest to describe reality, maps tell stories. They help construct a history in which they are a part. I like all of these things, especially stories.

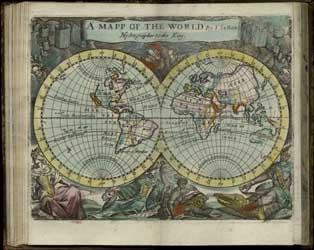

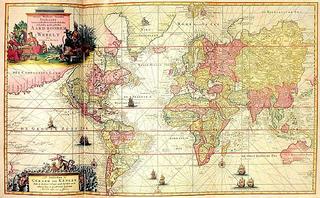

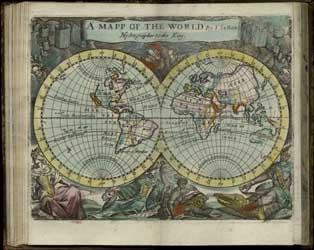

It is self-evident that the only true and accurate map of the world is a three-dimensional one. Yet, mapmakers have persistently striven to re-create the world on paper. Why? Is it simply because of the portability of a roll of parchment or vellum? Or, is it also the desire to see an image of the earth focused before us, clear, self-contained, comprehensible, and masterable? The paradox of this question is distilled within the cartographic language itself. The task, then, is to describe and interpret that language.

This essay explores the ontological nature of maps in two short parts. Part One, Believing is Seeing, focuses a medieval example of how people influence what maps show. In Part Two, Seeing is Believing, a map described by Herodotus from ancient Greek history shows how iconography can influence the behavior of people. In both cases, we see that maps help to construct a history, serve our interests, render visible that which is invisible, and interestingly, maps lie to us.

PART ONE - Believing is Seeing

The legend of Prestor John, a powerful Christian priest-king of unimaginable wealth and power, began in the 1030's, just before the start of the Great Crusades. This timing is not a coincidence. Maps that showed the kingdom of Prestor John contributed to the compulsory drive of the Crusades. And by the 12th century such maps clearly show a fictitious empire describe as belonging to Prestor John. These maps, however, show lands that had not yet been explored by western cartographers. They were, in fact, often completely imaginary.

In a lengthy letter supposedly written by the great monarch himself and sent to Emperor Manuel Commenus of Byzantine, Prestor John says, “…believe without doubting that I, Presbyter Ioannes, who reign[s] supreme, exceed[s] in riches, virtue, and power [over] all creatures who dwell under heaven … am a devout Christian and everywhere protect the Christians of our empire.”

The empire of Prestor John was a wondrous place which stretched from “the valley of deserted Babylon close by the Tower of Babel” to include “the Three Indias”. “Honey flows in our land, and milk everywhere abounds … In one of our territories no poison can do harm.” The river Physon, which “emerges[s] from Paradise”, is pebbled with diamonds, emeralds, and “many other precious stones.” There is even “a sandy sea without water. For the sand moves and swells into waves like the sea and is never still.” 1

To the medieval mind such a Christian ruler of immense riches and power would have made an ideal ally. For they feared the armies of Gog and Magog “shalt come from thy place out of the north parts, all of them riding upon horses, a great company … [that] shalt come up against my people of Israel, as a cloud to cover the land” (Ezekiel 38:15-16). The threat of an onslaught by Satan’s soldiers only strengthened the story of Prestor John, who, in his letter, vowed to “everywhere protect the Christians” with an army of “ten thousand mounted soldiers and one hundred thousand infantrymen.”

Kings sent ambassadors into these unknown, yet mapped, lands in search of the great monarch. Priests and popes sent missionaries. At first Prestor John’s kingdom was thought to be in India, and maps of India cropped up all over Europe. In 1245 the Franciscan monk John of Plam Carpini traveled across Poland, Russia, and into Central Asia looking for India. After riding by donkey for over 100 days, Friar John arrived in the land of the Mongols and Genghis Khan. It was reported back that it was from there that the armies of Gog and Magog would be unleashed. But nowhere in that vast land was Prestor John to be found. (Starting some years later, the Mongols sacked Baghdad.)

Soon the search spread into the Near East. By the 14th century, when the Near East and India did not prove to hold the magic and wealth by now described on many travel maps, mapmakers too reluctant to discard the legend began to draw Prestor John’s kingdom in Abyssinia, now modern day Ethiopia. Once the new maps began to circulate, many envoys deep into Africa followed.

Countless crusades and exploratory excursions into the Far East, India, and Africa did not turn up the mystic Christian monarch. However, they did establish trading routines for new goods, and for the development of cartography the crusades provided a better understanding of the geography outside of Europe. And thus the isolation of medieval Europe came to an end. As economic and civil sectors boomed, the once mighty alliance that was to be made with Prestor John against the armies of Gog and Magog, and the maps depicting his kidgdom, faded into the recesses of memory.

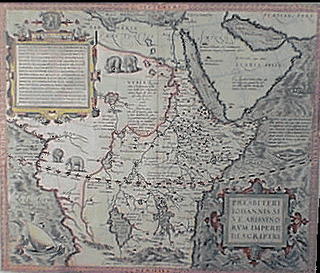

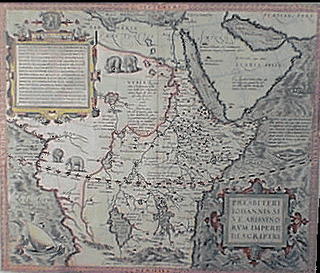

The most interesting characteristic displayed by this cartographical example is the general willingness of mapmakers to render parts of the world for which they had no geographical information. What they did know for certain about these places they mapped with some accuracy and attention. For example, a comparison of Ortelius’ map of Prestor John’s kingdom (above) to a contemporary map of central Africa shows that a lot of geographical information about Africa’s coastline was known at that time. However, what was not known was the deep interior of the continent, and that was ignored or completely fabricated. In thia unknown realm of Prestor John of central Africa, emblems of townships and holdings dot the map. Rivers and lakes are populated by these townships, supposedly a part of the kingdom. Areas not well known andnot considered a part of the kingdom were left plank or covered with signage (for example, from northwest to central western Africa). Southern Africa, being almost completely unexplored at the time by Europeans, was often left off maps completely.

Maps of Prestor John’s world were created for many reasons, some of which included mythical stories, religions, and political and economic goals. Such readiness to fabricate the world, or to replace a lack of knowledge about the world with inspired knowledge, under these kinds of social forces may be found on maps dating back the 6th century BCE. And within this we find one of the circular functions of maps: that people influence what maps represent in order to influence what people do.

PART TWO - Believing is Seeing

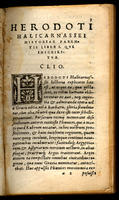

In 499-494 BCE an attempt was made to gain support for the Ionian Revolt against the Persians. According to the Greek historian Herodotus, a Greek by the name of Aristogoras of Miletus, the leader of the Ionian revolt, traveled to Sparta to win over the help of its dominant military power. Aristagorias’ tool of persuasion was a map.

The map was that of the known world at the time. It showed “all the seas and rivers”. It was a bronze tablet by Hecataeus. In the throne room of Cleomenes, Aristagoras made an appeal to the Spartan leader’s greed by pointing to all the lands and riches on the map which could be his if only he committed his arms to the revolt. As Aristagoras spoke, he pointed on the map of the world.

“Cleomenes, be not amazed at the eagerness of my coming here. The circumstances are these: that the children of the Ionians should be slaves instead of free men is the greatest of reproaches to ourselves, and, of all the rest of men, especially of you, inasmuch as you are the leader of Greece … What is more, these men [Persians] who live on that continent have an abundance of good things such as not all other men together have—beginning with gold, and then silver, and bronze, and dyed raiment, and beast of burden, and slaves. You may have of these all your heart’s desire. They live, too, next to one another, as I can show you [on the map]: here are the Lydians, right next to the Ionians, living in a fertile land, and they have much silver among them.”

“Cleomenes, be not amazed at the eagerness of my coming here. The circumstances are these: that the children of the Ionians should be slaves instead of free men is the greatest of reproaches to ourselves, and, of all the rest of men, especially of you, inasmuch as you are the leader of Greece … What is more, these men [Persians] who live on that continent have an abundance of good things such as not all other men together have—beginning with gold, and then silver, and bronze, and dyed raiment, and beast of burden, and slaves. You may have of these all your heart’s desire. They live, too, next to one another, as I can show you [on the map]: here are the Lydians, right next to the Ionians, living in a fertile land, and they have much silver among them.”

Once the lands of the Lydian, which bordered Greece, were “shown” as being wealthy, he pointed farther east, and spoke of other riches.

“And here, next to the Lydian,” said Aristagoars, “are the Phrygians, to the east, with more flocks than any people on earth that I know and with greater crops. Next to the Phyrgians are the Cappadocians, whom we call Syrians. On their borders are the Cilicians, whose land comes down to the sea right here, where the island of Cyprus lies. Fifty talents are what they contribute to the Great King yearly. Next [to] the Cilicians are the Armenians, here—they, too, are rich in herds—and next [to] the Armenians are the Matieni, who live in this country. Next [to] them is the Cissian land, and in it, by this river, the Choapers, in Susa, where the Great King has his lodging and where his treasure houses are. Capture that city and you may well boast that you rival Zeus in wealth.”

Enticed, Cleomenes inquired, smartly, “how many days journey it was from the Ionian sea to where the Great King was.” Here, Herodotus implies that up to his point Aristagoras’ claims about the mapped lands were fraudulent, for “In everything else Aristagoras was very clever and had tricked Cleomenes successfully, but here he tripped up.” In answering the questions of distance, Aristagoras told the truth. When Cleomanese heard that the journey would take at least three months, he refused to commit Spartan soldiers to such a conquest.

No early world maps from Greece have survived, but the story told by Herodotus suggests several points of interests. First, a map is an effective tool for categorizing objects (lands, people, treasures) into separate domains. The Lydians live here, the Phrygians there, and so on. Respectively, with the Lydians are fertile lands and silver; the Phrygians hold great flocks and crops; there are more riches elsewhere. In the act of looking at maps, one is better able to make a correlation between objects and the ideas, desires, processes, or goals towards those objects through the spatial relationships that maps construct.

Second, as a representation of what is not otherwise available to the viewer (such as future goals or possessions), maps can be misleading or even fully deceptive in what they show. In the represenation of objects or goals in written or iconographic form, we tend to give those representations more turth than actually exsist in reality. This is also illustrated in the first cartographic example by Ortelius. Where as the map described by Aristagoras was used to deceive for a purpose, maps of Prestor John’s kingdom were not intended to deceive, but render real what was imagined. Both kinds of maps were meant to influence the people who viewed them, however.

Third, the concept of a map of the world drawn to scale was unfamiliar in ancient times. An awareness of the relationship between spatial distance and time of travel was not easily conciliated into a reality. Rather, an awareness of spatial arrangement of relatedness seems more fundamental than that of time, even today. With Aristagoras’ map, Cleomenes is better able to view the spatial relationship between his kingdom and that of the Great King in Susa, but not the amount of time it would take to travel there. This is a charcateristic of human temporal perception today as well.

And forth, as an extension of the last, the reason for the use of mapping as a metaphor for knowing or communicating becomes clear: the concept of spatial relatedness is a quality without which it is difficult for the human mind to apprehend objects of knowledge. Whether one is trying to comprehend something unknown or trying to make unknown things a reality by using maps to illustrate them, in both of the above examples, the human mind endeavors to spatially place things into a relationship to itself as a means of understanding.

The characteristics outlined above are not conclusive, nor are they exclusive qualities of maps. The characteristics may be found in both examples. They are in fact true of all maps from ancient times to present day cartography (think of political maps, for the most transparent example).

“If anyone considers incredible the unheard-of things I have set down here, let him do homage to the secrets of nature, rather than consult his intellect. For nature conceives of innumerable things, of which those know to us are fewer than those not known, and this is so because nature exceeds understanding.” — Fra Mauro, medieval mapmaker

1 As quoted from a translation of The realm of Prestor John by Silverberg.

Downs © Copyright 2005

Related Post: Jan Vameer's The Art of Painting

I love maps. I am interested in them because they embody many of the things I like. Maps are cultural artifacts comparable to diaries, art objects, literature, or musical instruments. Almost every culture had developed maps, but they did it with enormously varying degrees of sophistication. The origin of maps seems instinctive, in that they are products both of the intellect and the imagination confronting problems in reality. That is, in the quest to describe reality, maps tell stories. They help construct a history in which they are a part. I like all of these things, especially stories.

I love maps. I am interested in them because they embody many of the things I like. Maps are cultural artifacts comparable to diaries, art objects, literature, or musical instruments. Almost every culture had developed maps, but they did it with enormously varying degrees of sophistication. The origin of maps seems instinctive, in that they are products both of the intellect and the imagination confronting problems in reality. That is, in the quest to describe reality, maps tell stories. They help construct a history in which they are a part. I like all of these things, especially stories.It is self-evident that the only true and accurate map of the world is a three-dimensional one. Yet, mapmakers have persistently striven to re-create the world on paper. Why? Is it simply because of the portability of a roll of parchment or vellum? Or, is it also the desire to see an image of the earth focused before us, clear, self-contained, comprehensible, and masterable? The paradox of this question is distilled within the cartographic language itself. The task, then, is to describe and interpret that language.

This essay explores the ontological nature of maps in two short parts. Part One, Believing is Seeing, focuses a medieval example of how people influence what maps show. In Part Two, Seeing is Believing, a map described by Herodotus from ancient Greek history shows how iconography can influence the behavior of people. In both cases, we see that maps help to construct a history, serve our interests, render visible that which is invisible, and interestingly, maps lie to us.

PART ONE - Believing is Seeing

The legend of Prestor John, a powerful Christian priest-king of unimaginable wealth and power, began in the 1030's, just before the start of the Great Crusades. This timing is not a coincidence. Maps that showed the kingdom of Prestor John contributed to the compulsory drive of the Crusades. And by the 12th century such maps clearly show a fictitious empire describe as belonging to Prestor John. These maps, however, show lands that had not yet been explored by western cartographers. They were, in fact, often completely imaginary.

In a lengthy letter supposedly written by the great monarch himself and sent to Emperor Manuel Commenus of Byzantine, Prestor John says, “…believe without doubting that I, Presbyter Ioannes, who reign[s] supreme, exceed[s] in riches, virtue, and power [over] all creatures who dwell under heaven … am a devout Christian and everywhere protect the Christians of our empire.”

The empire of Prestor John was a wondrous place which stretched from “the valley of deserted Babylon close by the Tower of Babel” to include “the Three Indias”. “Honey flows in our land, and milk everywhere abounds … In one of our territories no poison can do harm.” The river Physon, which “emerges[s] from Paradise”, is pebbled with diamonds, emeralds, and “many other precious stones.” There is even “a sandy sea without water. For the sand moves and swells into waves like the sea and is never still.” 1

To the medieval mind such a Christian ruler of immense riches and power would have made an ideal ally. For they feared the armies of Gog and Magog “shalt come from thy place out of the north parts, all of them riding upon horses, a great company … [that] shalt come up against my people of Israel, as a cloud to cover the land” (Ezekiel 38:15-16). The threat of an onslaught by Satan’s soldiers only strengthened the story of Prestor John, who, in his letter, vowed to “everywhere protect the Christians” with an army of “ten thousand mounted soldiers and one hundred thousand infantrymen.”

Kings sent ambassadors into these unknown, yet mapped, lands in search of the great monarch. Priests and popes sent missionaries. At first Prestor John’s kingdom was thought to be in India, and maps of India cropped up all over Europe. In 1245 the Franciscan monk John of Plam Carpini traveled across Poland, Russia, and into Central Asia looking for India. After riding by donkey for over 100 days, Friar John arrived in the land of the Mongols and Genghis Khan. It was reported back that it was from there that the armies of Gog and Magog would be unleashed. But nowhere in that vast land was Prestor John to be found. (Starting some years later, the Mongols sacked Baghdad.)

Soon the search spread into the Near East. By the 14th century, when the Near East and India did not prove to hold the magic and wealth by now described on many travel maps, mapmakers too reluctant to discard the legend began to draw Prestor John’s kingdom in Abyssinia, now modern day Ethiopia. Once the new maps began to circulate, many envoys deep into Africa followed.

Countless crusades and exploratory excursions into the Far East, India, and Africa did not turn up the mystic Christian monarch. However, they did establish trading routines for new goods, and for the development of cartography the crusades provided a better understanding of the geography outside of Europe. And thus the isolation of medieval Europe came to an end. As economic and civil sectors boomed, the once mighty alliance that was to be made with Prestor John against the armies of Gog and Magog, and the maps depicting his kidgdom, faded into the recesses of memory.

The most interesting characteristic displayed by this cartographical example is the general willingness of mapmakers to render parts of the world for which they had no geographical information. What they did know for certain about these places they mapped with some accuracy and attention. For example, a comparison of Ortelius’ map of Prestor John’s kingdom (above) to a contemporary map of central Africa shows that a lot of geographical information about Africa’s coastline was known at that time. However, what was not known was the deep interior of the continent, and that was ignored or completely fabricated. In thia unknown realm of Prestor John of central Africa, emblems of townships and holdings dot the map. Rivers and lakes are populated by these townships, supposedly a part of the kingdom. Areas not well known andnot considered a part of the kingdom were left plank or covered with signage (for example, from northwest to central western Africa). Southern Africa, being almost completely unexplored at the time by Europeans, was often left off maps completely.

Maps of Prestor John’s world were created for many reasons, some of which included mythical stories, religions, and political and economic goals. Such readiness to fabricate the world, or to replace a lack of knowledge about the world with inspired knowledge, under these kinds of social forces may be found on maps dating back the 6th century BCE. And within this we find one of the circular functions of maps: that people influence what maps represent in order to influence what people do.

PART TWO - Believing is Seeing

In 499-494 BCE an attempt was made to gain support for the Ionian Revolt against the Persians. According to the Greek historian Herodotus, a Greek by the name of Aristogoras of Miletus, the leader of the Ionian revolt, traveled to Sparta to win over the help of its dominant military power. Aristagorias’ tool of persuasion was a map.

The map was that of the known world at the time. It showed “all the seas and rivers”. It was a bronze tablet by Hecataeus. In the throne room of Cleomenes, Aristagoras made an appeal to the Spartan leader’s greed by pointing to all the lands and riches on the map which could be his if only he committed his arms to the revolt. As Aristagoras spoke, he pointed on the map of the world.

“Cleomenes, be not amazed at the eagerness of my coming here. The circumstances are these: that the children of the Ionians should be slaves instead of free men is the greatest of reproaches to ourselves, and, of all the rest of men, especially of you, inasmuch as you are the leader of Greece … What is more, these men [Persians] who live on that continent have an abundance of good things such as not all other men together have—beginning with gold, and then silver, and bronze, and dyed raiment, and beast of burden, and slaves. You may have of these all your heart’s desire. They live, too, next to one another, as I can show you [on the map]: here are the Lydians, right next to the Ionians, living in a fertile land, and they have much silver among them.”

“Cleomenes, be not amazed at the eagerness of my coming here. The circumstances are these: that the children of the Ionians should be slaves instead of free men is the greatest of reproaches to ourselves, and, of all the rest of men, especially of you, inasmuch as you are the leader of Greece … What is more, these men [Persians] who live on that continent have an abundance of good things such as not all other men together have—beginning with gold, and then silver, and bronze, and dyed raiment, and beast of burden, and slaves. You may have of these all your heart’s desire. They live, too, next to one another, as I can show you [on the map]: here are the Lydians, right next to the Ionians, living in a fertile land, and they have much silver among them.”Once the lands of the Lydian, which bordered Greece, were “shown” as being wealthy, he pointed farther east, and spoke of other riches.

“And here, next to the Lydian,” said Aristagoars, “are the Phrygians, to the east, with more flocks than any people on earth that I know and with greater crops. Next to the Phyrgians are the Cappadocians, whom we call Syrians. On their borders are the Cilicians, whose land comes down to the sea right here, where the island of Cyprus lies. Fifty talents are what they contribute to the Great King yearly. Next [to] the Cilicians are the Armenians, here—they, too, are rich in herds—and next [to] the Armenians are the Matieni, who live in this country. Next [to] them is the Cissian land, and in it, by this river, the Choapers, in Susa, where the Great King has his lodging and where his treasure houses are. Capture that city and you may well boast that you rival Zeus in wealth.”

Enticed, Cleomenes inquired, smartly, “how many days journey it was from the Ionian sea to where the Great King was.” Here, Herodotus implies that up to his point Aristagoras’ claims about the mapped lands were fraudulent, for “In everything else Aristagoras was very clever and had tricked Cleomenes successfully, but here he tripped up.” In answering the questions of distance, Aristagoras told the truth. When Cleomanese heard that the journey would take at least three months, he refused to commit Spartan soldiers to such a conquest.

No early world maps from Greece have survived, but the story told by Herodotus suggests several points of interests. First, a map is an effective tool for categorizing objects (lands, people, treasures) into separate domains. The Lydians live here, the Phrygians there, and so on. Respectively, with the Lydians are fertile lands and silver; the Phrygians hold great flocks and crops; there are more riches elsewhere. In the act of looking at maps, one is better able to make a correlation between objects and the ideas, desires, processes, or goals towards those objects through the spatial relationships that maps construct.

Second, as a representation of what is not otherwise available to the viewer (such as future goals or possessions), maps can be misleading or even fully deceptive in what they show. In the represenation of objects or goals in written or iconographic form, we tend to give those representations more turth than actually exsist in reality. This is also illustrated in the first cartographic example by Ortelius. Where as the map described by Aristagoras was used to deceive for a purpose, maps of Prestor John’s kingdom were not intended to deceive, but render real what was imagined. Both kinds of maps were meant to influence the people who viewed them, however.

Third, the concept of a map of the world drawn to scale was unfamiliar in ancient times. An awareness of the relationship between spatial distance and time of travel was not easily conciliated into a reality. Rather, an awareness of spatial arrangement of relatedness seems more fundamental than that of time, even today. With Aristagoras’ map, Cleomenes is better able to view the spatial relationship between his kingdom and that of the Great King in Susa, but not the amount of time it would take to travel there. This is a charcateristic of human temporal perception today as well.

And forth, as an extension of the last, the reason for the use of mapping as a metaphor for knowing or communicating becomes clear: the concept of spatial relatedness is a quality without which it is difficult for the human mind to apprehend objects of knowledge. Whether one is trying to comprehend something unknown or trying to make unknown things a reality by using maps to illustrate them, in both of the above examples, the human mind endeavors to spatially place things into a relationship to itself as a means of understanding.

The characteristics outlined above are not conclusive, nor are they exclusive qualities of maps. The characteristics may be found in both examples. They are in fact true of all maps from ancient times to present day cartography (think of political maps, for the most transparent example).

“If anyone considers incredible the unheard-of things I have set down here, let him do homage to the secrets of nature, rather than consult his intellect. For nature conceives of innumerable things, of which those know to us are fewer than those not known, and this is so because nature exceeds understanding.” — Fra Mauro, medieval mapmaker

1 As quoted from a translation of The realm of Prestor John by Silverberg.

Downs © Copyright 2005

Related Post: Jan Vameer's The Art of Painting

Monday, October 17, 2005

Wednesday, October 05, 2005

Saturday, October 01, 2005

Jan Vermeer’s The Art of Painting

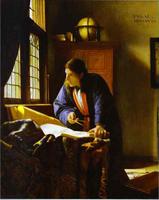

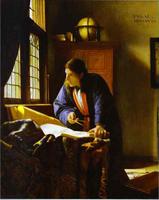

In his allegorical work, The Art of Painting, Jan Vermeer gives the map of the Netherlands a central place on the canvas. The figure of a young woman stands just before it, draped in blue and holding a trumpet and a book. She poses, taking on the role of representing History. The image of History, an event that necessarily calls for interpretation, is thus juxtaposed with the map of a history of the Netherlands. The map, which we see is like a painting, is also a version of history. It records the Netherlands as transformed by the towns, bridges and towers of human endeavor, as well as by the craft of mapmaking. This transformation is situated behind History, and she, interestingly, has her back to it, not because she disregards it, but because she has no part in what or how history is represented. Instead, she faces us and the artist.

In his allegorical work, The Art of Painting, Jan Vermeer gives the map of the Netherlands a central place on the canvas. The figure of a young woman stands just before it, draped in blue and holding a trumpet and a book. She poses, taking on the role of representing History. The image of History, an event that necessarily calls for interpretation, is thus juxtaposed with the map of a history of the Netherlands. The map, which we see is like a painting, is also a version of history. It records the Netherlands as transformed by the towns, bridges and towers of human endeavor, as well as by the craft of mapmaking. This transformation is situated behind History, and she, interestingly, has her back to it, not because she disregards it, but because she has no part in what or how history is represented. Instead, she faces us and the artist. We see now that the image is laden with both the events that the discourse of history wishes to describe and the function of description itself.

We see now that the image is laden with both the events that the discourse of history wishes to describe and the function of description itself. In contrast, the artist sits with his back to us, anonymous and faceless. His eyes are buried and hidden by his task. Who is this person who is recording History? One cannot discern to where his attention is directed: is it the model or the canvas—History or representing History? He is lost within the very world which he represents, simultaneously between History and recording it on his canvas.

In contrast, the artist sits with his back to us, anonymous and faceless. His eyes are buried and hidden by his task. Who is this person who is recording History? One cannot discern to where his attention is directed: is it the model or the canvas—History or representing History? He is lost within the very world which he represents, simultaneously between History and recording it on his canvas.Similarly, we, the viewers, are left suspended in a dim light. We are pushed back and away from the world being represented by a drapery that hangs between the outside world and that of the painting. We repeat the task of the painter, for we are removed from our subjects and we are now confronted with the task of interpreting them. So then, are we removed from the act of representing history as well, like the painter? Is not to look at a painting the act of interpretation of a history, its history?

Together, the woman as History with the map as historical emblem and the painter, set forth the multi-faced cycles of the image. First, the art of the painting contains within itself the impulse to map or describe, and visa-versa. Second, observation is shown to be inseparable from the act of representing, or the interpretation and the recording of history. And third, the events of history themselves are impossible to encounter or fully grasp.

Downs - Copyright © 2005

Related Post: The Nature of Maps

Tuesday, September 27, 2005

Monday, September 26, 2005

Sketches of What Made the 50's

Albert Einstein’s Spaceman in an Elevator

In 1955 Einstein died without ever finding his man in an elevator. It is a search that may well extend into the next millennium. If a man in an elevator couldn’t feel his own weight in space, Einstein pondered, then what does he feel when the elevator is accelerating through space? Something like weight, but not quite. It has something to do with vibrating superstrings, physicists say. At about the same time as Einstein’s death, the artist Jasper Johns does something interesting. He paints the man in the elevator. Well, okay, not exactly. Actually, Johns started painting images of the American flag, then later he painted images of numbers, and targets, but the idea is the same as Einstein’s elevator man: that it’s just an idea and there it is, gravity or whatever. It doesn’t have any real form.

In 1955 Einstein died without ever finding his man in an elevator. It is a search that may well extend into the next millennium. If a man in an elevator couldn’t feel his own weight in space, Einstein pondered, then what does he feel when the elevator is accelerating through space? Something like weight, but not quite. It has something to do with vibrating superstrings, physicists say. At about the same time as Einstein’s death, the artist Jasper Johns does something interesting. He paints the man in the elevator. Well, okay, not exactly. Actually, Johns started painting images of the American flag, then later he painted images of numbers, and targets, but the idea is the same as Einstein’s elevator man: that it’s just an idea and there it is, gravity or whatever. It doesn’t have any real form.

Hey, Charles Lindbergh Was a Nazi

Sometimes I get sick. The higher I go the more dizzying the view is out of glass elevators. But some people are amazing because they just aren’t bothered by heights. Either they never look out the window to see where they are, or maybe they don’t see anything when they do look. I’m not sure why, but it makes me think of Charles Lindbergh. He’s famous because of this, for flying the Spirit of St. Louis across the Atlantic Ocean, from New York to Paris in 1927. He’s remembered as a daring aviator and an American hero. But people have forgotten, even after WWII, that this hero was a white supremacist and advocator of Nazism. Some people can go higher than others. And when he landed in Paris, it really wasn’t Lindbergh the world cheered for, it was for what he did. That’s always the case, I suppose. So there’s no real form there either. But the other weird thing is that perhaps the most important fact about contemporary times after the Second World War is that they were always going to be different soon. In the 50’s, they could have shot off in any direction. Anyone who could do it flew that plane in some way or another.

Beethoven and Politics

Beethoven was actually afraid of heights. He was the kind of man who would move between five different apartments, each one with a piano in it, shifting every time any one of his friends discovered in which apartment he was staying. For him, music was everything. I mean so much everything that the only thing that stopped him from creating more of it was death. And in his later years, when he composed, he would press his stone-deaf head up against his piano and write music by the feel of its vibrations. It was the reverse of poetry, if you think about it. I mean, if poetry strives toward being music, for Beethoven there was no music, only the poetry of vibrating springs, which I guess gave him music again. Well, whatever it was, it was what he believed in, and this thing he believed in vibrated through his skull. But it wasn’t tangible.

Beethoven was actually afraid of heights. He was the kind of man who would move between five different apartments, each one with a piano in it, shifting every time any one of his friends discovered in which apartment he was staying. For him, music was everything. I mean so much everything that the only thing that stopped him from creating more of it was death. And in his later years, when he composed, he would press his stone-deaf head up against his piano and write music by the feel of its vibrations. It was the reverse of poetry, if you think about it. I mean, if poetry strives toward being music, for Beethoven there was no music, only the poetry of vibrating springs, which I guess gave him music again. Well, whatever it was, it was what he believed in, and this thing he believed in vibrated through his skull. But it wasn’t tangible.

EE Cummings and Death

In about 1950, Cummings wrote this poem:

dying is fine)but Death

?o

baby

i

wouldn’t like

Death if Death

were

good….

because dying is natural….

Death

is strictly

scientific

& artificial &

evil & legal)

We fear death, yet we long for slumber and beautiful dreams. Death is a strange thing. And it is probably the most patient thing, too. As Cummings mentions, excluding what we don’t know about the rest of the universe and existence, dying is natural but death is an exclusively human experience. This is because we know that we will die. And aren’t death and dying clean two different things? Dying, well, we don’t really care about that until it’s accelerated by disease or circumstance. Dying starts at conception, and we call it life. It’s great. But death, that’s the one thing that separates humans from other animals. Since we know we will die, we make a big deal out of it while dying. That’s why we make so much art, have so many religions, make so many artifacts that possess the durability that we just don’t have. And when the H-bomb was tested in ’52, the crowning achievement of men like Einstein looking for men in space elevators, a new idea presented itself: if every human died, then wouldn’t that mean that death would die?

Jackson Pollock and DNA

So you have to envy Pollock in a way. He probably never died, if it was an instant thing, but then again I don’t know the details of his accident. But while he was dying, that is while he was alive, he may have exposed a fundamental contradiction between the legacy of our genes and our experiences in the world. You see, when the structure of DNA was discovered in ’53, biologists thought up another weird idea. Biological bodies were never meant to survive. Only the DNA strings within us all will persist through time. They hold together the information of millions of years of dying. When we die, their code goes on in some other biological body. And superstrings are thought to hold the universe together in the same way too. They call it superstring gravity theory, a cosmic blueprint of everything vibrating in some ambiguous, separate, curved space. Pollock had been painting an ambiguous place, too, and he filled it with seemingly endless calligraphy, making an archeology of time, dripping strings of paint with gravity pulling it down into a layered landscape. Is there a connection?

Hell, I doubt it. But anything could have made sense in the 50’s, in some strange way, if you wanted it to. All those witty ads and Hollywood movies, always looking for something else, even the absurdity of life within the anguish of death—it’s like catching yourself breathe while dead. Right after WWII and into Korea, that was America, left standing to watch the rise of a nuclear age as well as a Cold War. So I suppose anything could make sense in a decade when the most tangible thing in the western world was a man hurdling through space in an elevator. Sure, there were the shutter of an invisible Iron Curtain and the Berlin Wall in ’61, but they aren’t poetry, no matter how much it shook anyone’s skull.

Downs © Copyright 2005

In 1955 Einstein died without ever finding his man in an elevator. It is a search that may well extend into the next millennium. If a man in an elevator couldn’t feel his own weight in space, Einstein pondered, then what does he feel when the elevator is accelerating through space? Something like weight, but not quite. It has something to do with vibrating superstrings, physicists say. At about the same time as Einstein’s death, the artist Jasper Johns does something interesting. He paints the man in the elevator. Well, okay, not exactly. Actually, Johns started painting images of the American flag, then later he painted images of numbers, and targets, but the idea is the same as Einstein’s elevator man: that it’s just an idea and there it is, gravity or whatever. It doesn’t have any real form.

In 1955 Einstein died without ever finding his man in an elevator. It is a search that may well extend into the next millennium. If a man in an elevator couldn’t feel his own weight in space, Einstein pondered, then what does he feel when the elevator is accelerating through space? Something like weight, but not quite. It has something to do with vibrating superstrings, physicists say. At about the same time as Einstein’s death, the artist Jasper Johns does something interesting. He paints the man in the elevator. Well, okay, not exactly. Actually, Johns started painting images of the American flag, then later he painted images of numbers, and targets, but the idea is the same as Einstein’s elevator man: that it’s just an idea and there it is, gravity or whatever. It doesn’t have any real form.Hey, Charles Lindbergh Was a Nazi

Sometimes I get sick. The higher I go the more dizzying the view is out of glass elevators. But some people are amazing because they just aren’t bothered by heights. Either they never look out the window to see where they are, or maybe they don’t see anything when they do look. I’m not sure why, but it makes me think of Charles Lindbergh. He’s famous because of this, for flying the Spirit of St. Louis across the Atlantic Ocean, from New York to Paris in 1927. He’s remembered as a daring aviator and an American hero. But people have forgotten, even after WWII, that this hero was a white supremacist and advocator of Nazism. Some people can go higher than others. And when he landed in Paris, it really wasn’t Lindbergh the world cheered for, it was for what he did. That’s always the case, I suppose. So there’s no real form there either. But the other weird thing is that perhaps the most important fact about contemporary times after the Second World War is that they were always going to be different soon. In the 50’s, they could have shot off in any direction. Anyone who could do it flew that plane in some way or another.

Beethoven and Politics

Beethoven was actually afraid of heights. He was the kind of man who would move between five different apartments, each one with a piano in it, shifting every time any one of his friends discovered in which apartment he was staying. For him, music was everything. I mean so much everything that the only thing that stopped him from creating more of it was death. And in his later years, when he composed, he would press his stone-deaf head up against his piano and write music by the feel of its vibrations. It was the reverse of poetry, if you think about it. I mean, if poetry strives toward being music, for Beethoven there was no music, only the poetry of vibrating springs, which I guess gave him music again. Well, whatever it was, it was what he believed in, and this thing he believed in vibrated through his skull. But it wasn’t tangible.

Beethoven was actually afraid of heights. He was the kind of man who would move between five different apartments, each one with a piano in it, shifting every time any one of his friends discovered in which apartment he was staying. For him, music was everything. I mean so much everything that the only thing that stopped him from creating more of it was death. And in his later years, when he composed, he would press his stone-deaf head up against his piano and write music by the feel of its vibrations. It was the reverse of poetry, if you think about it. I mean, if poetry strives toward being music, for Beethoven there was no music, only the poetry of vibrating springs, which I guess gave him music again. Well, whatever it was, it was what he believed in, and this thing he believed in vibrated through his skull. But it wasn’t tangible.EE Cummings and Death

In about 1950, Cummings wrote this poem:

dying is fine)but Death

?o

baby

i

wouldn’t like

Death if Death

were

good….

because dying is natural….

Death

is strictly

scientific

& artificial &

evil & legal)

We fear death, yet we long for slumber and beautiful dreams. Death is a strange thing. And it is probably the most patient thing, too. As Cummings mentions, excluding what we don’t know about the rest of the universe and existence, dying is natural but death is an exclusively human experience. This is because we know that we will die. And aren’t death and dying clean two different things? Dying, well, we don’t really care about that until it’s accelerated by disease or circumstance. Dying starts at conception, and we call it life. It’s great. But death, that’s the one thing that separates humans from other animals. Since we know we will die, we make a big deal out of it while dying. That’s why we make so much art, have so many religions, make so many artifacts that possess the durability that we just don’t have. And when the H-bomb was tested in ’52, the crowning achievement of men like Einstein looking for men in space elevators, a new idea presented itself: if every human died, then wouldn’t that mean that death would die?

Jackson Pollock and DNA

So you have to envy Pollock in a way. He probably never died, if it was an instant thing, but then again I don’t know the details of his accident. But while he was dying, that is while he was alive, he may have exposed a fundamental contradiction between the legacy of our genes and our experiences in the world. You see, when the structure of DNA was discovered in ’53, biologists thought up another weird idea. Biological bodies were never meant to survive. Only the DNA strings within us all will persist through time. They hold together the information of millions of years of dying. When we die, their code goes on in some other biological body. And superstrings are thought to hold the universe together in the same way too. They call it superstring gravity theory, a cosmic blueprint of everything vibrating in some ambiguous, separate, curved space. Pollock had been painting an ambiguous place, too, and he filled it with seemingly endless calligraphy, making an archeology of time, dripping strings of paint with gravity pulling it down into a layered landscape. Is there a connection?

Hell, I doubt it. But anything could have made sense in the 50’s, in some strange way, if you wanted it to. All those witty ads and Hollywood movies, always looking for something else, even the absurdity of life within the anguish of death—it’s like catching yourself breathe while dead. Right after WWII and into Korea, that was America, left standing to watch the rise of a nuclear age as well as a Cold War. So I suppose anything could make sense in a decade when the most tangible thing in the western world was a man hurdling through space in an elevator. Sure, there were the shutter of an invisible Iron Curtain and the Berlin Wall in ’61, but they aren’t poetry, no matter how much it shook anyone’s skull.

Downs © Copyright 2005

Saturday, September 24, 2005

Thursday, September 22, 2005

Film Critique - Grizzly Man

Werner Herzog's documentary film Grizzly Man explores a fine line between society and nature through an amazing portrait of the late environmentalist, Timothy Treadwell. Treadwell dedicated his life to what he thought was the necessary protection of grizzly bears in the Alaskan wilderness. He spent 13 summers living with the bears, often with surprisingly close interaction, vowing to protect them from poachers. He saw himself as their friend—“the kind warrior”—who stood by their side against the dangers of an encroaching society. But in an ironic twist of fate, in October 2003 Treadwell was devoured by one of the bears that he dedicated his life to protect.

Werner Herzog's documentary film Grizzly Man explores a fine line between society and nature through an amazing portrait of the late environmentalist, Timothy Treadwell. Treadwell dedicated his life to what he thought was the necessary protection of grizzly bears in the Alaskan wilderness. He spent 13 summers living with the bears, often with surprisingly close interaction, vowing to protect them from poachers. He saw himself as their friend—“the kind warrior”—who stood by their side against the dangers of an encroaching society. But in an ironic twist of fate, in October 2003 Treadwell was devoured by one of the bears that he dedicated his life to protect.This is a beautiful film. One is surprised by its calm, especially when one preceives the violent subject matter and the tragic turn of events. But it is not entirely the film’s portrait of Timothy Treadwell that is so engaging and beautiful. What is most captivating is the amazing self-portrait as documented by Treadmill himself.

In his many hours of film, Treadwell captured himself with an honesty and transparency that is rare in even the most candid of documentary filmmaking. He becomes endearingly human. One wants to know him better as he playfully expressions humor, exposing his trouble with women and the world; he does not hide his pain and frustration with nature when a lack of rain and food forces the bears into cannibalism; and he openly shows his confusion, his increasingly bear-like behavior, and his growing hatred towards a society that he feels has rejected him entirely. Through monologues into his camera, we learn of a dark and troubled past, and as he wages an ironic war against human kind, we learn many confessions of an even darker present. Indeed, as the film replays Treadwell’s solitary life in the wild, we watch with eerie proximity the process of a man unfolding.

In my view, this is the absolute best film of the year.

Downs - Copyright © 2005

Monday, September 19, 2005

Film Critique - Broken Flowers

In Broken Flowers Bill Murray plays Don Johnston, an aging “Don Juan” who receives an anonymous letter which tells him that nearly 20 years ago he became a father. His supposed son has left on a mysterious road trip, perhaps to find his father. Murray's neighbor, Winston, takes on the mystery and sends Murray on a cross-country journey through past relationships to discover which one might be the mother of his son.

In Broken Flowers Bill Murray plays Don Johnston, an aging “Don Juan” who receives an anonymous letter which tells him that nearly 20 years ago he became a father. His supposed son has left on a mysterious road trip, perhaps to find his father. Murray's neighbor, Winston, takes on the mystery and sends Murray on a cross-country journey through past relationships to discover which one might be the mother of his son.There is no one who can perform “doing nothing” in the middle of everything better than Bill Murray, and he is able to convey thoughts and emotions with subtleness and purpose. As Murray meets with his former relationships, he approaches them with memories of the past; but, he is quickly confronted with the reality that lives change. It is a reality that is mired with surprises, disappointments, and new sentiments.

Many films explore exactly this interaction between time, memory, and perception. But the film’s director, Jim Barmusch, not only addresses this interplay with sophistication, he is also not afraid to delve deep into the complexity of the pain and confusion that surface with the memories. And it is not without fresh humor and witty turns of phrase. I find this film to be one of the best films of this year.

Downs - Copyright © 2005

Sunday, September 18, 2005

Saturday, September 17, 2005

Dragon Hunts

As a young knight I began each day wearily, overwhelmed by the distance I would have to cross, not knowing what I should expect to find within that distance. And each day, in my mind I fabricated dark corners of the world, hidden niches to seek out, and distant mountains to ascend. I would lose myself within the fantasia of this mental forest, jumping between entangled trees of thought, braving the landscape’s most perilous cliff or cave, becoming lost in a world become labyrinth, a delirium of darkness and shadows, inhabited by dragons of the fiercest kind.

In this world the most glorious of all possessions one could hope to have was that of the carbuncle. A carbuncle was a precious stone, a deep red ruby that is found buried in the brains of dragons. To obtain it, you had to do battle. If not taken fresh from a still living dragon, and in the complete absence of light, the carbuncle would dissolve into thin air. And if you were in possession of a carbuncle, if indeed, you dared to do battle with dragons in the dark, the stone would give you good fortune and everlasting magical power.

The hunt for dragons was always dangerous. The most cunning of warriors, even those who had traveled from the Far East, have been laid to waste by such merciless beasts. For small boys like myself, who were generally known at the time to be virtually invisible to even the keenest sighted dragon, the task was made no easier. Dragons often fed their young the tender meat of seven-year-olds, and unlike small girls and other people, little boys were very tasty. Thus the fact that dragons could not see a little boy meant close to nothing: dragons could still smell their sweet flesh and dragons could still hear their tiny feet like they could hear the breathe of butterflies, even as they slept.

The hunt for dragons was always dangerous. The most cunning of warriors, even those who had traveled from the Far East, have been laid to waste by such merciless beasts. For small boys like myself, who were generally known at the time to be virtually invisible to even the keenest sighted dragon, the task was made no easier. Dragons often fed their young the tender meat of seven-year-olds, and unlike small girls and other people, little boys were very tasty. Thus the fact that dragons could not see a little boy meant close to nothing: dragons could still smell their sweet flesh and dragons could still hear their tiny feet like they could hear the breathe of butterflies, even as they slept.Ambush was feeble. Confrontation was inevitable.

To do hand-to-hand battle with a dragon was the bravest thing you can do. It meant fighting the gnarly and the impossible, gnarly because the battle was always fought in the dark, and impossible because no one else saw the dragon like you saw the dragon. In doing battle with that which is unseen to others, as with doing art that is actually art, the best you can do is interpret the enigmatic; that is, you can only adjust yourself to it. And to interpret the enigmatic is to take a leap into an abyss, a leap from the material into the spiritual. It is awesome, and it is immeasurable.

The removal of a carbuncle was the trickiest of all procedures. First, the conditions had to be prefect if a carbuncle was not to vanish. The smallest intrusion of light, even the faintest flicker of starlight, into the deep regions of the dragon’s brain instantly dissolved the stone. Second, you had to master a remarkable craft. The stone was to be removed while enveloped between two of the dragons scales, both from the very top of its skull, a protective case tightly sewn together with the creature’s own whiskers. And once removed, if removed at all, a carbuncle could continue to exist only if properly kept safe in its case, safe from greed, safe from one’s own vanity, and safe from the disbelieve of others.

You never saw a carbuncle. You believed in it.

The very first time I heard about carbuncles, I was maybe five. The story was told to me by an old sailor of the Lough Foyle, like so many other stories I heard as a little boy. I’ve always considered this to be one of the most rewarding aspects of my short life history, that is, having grown up as a very young lad in the Northern Irish countryside, just east of Londonderry, and being told tales upon tales by old, bearded seafarers as they worked with their nets at the piers. They would leave early while the morning fog was still breathing, and by evening, if they hadn’t gone as far as Stranraer or even Oban, they would return with the most fantastic and curious stories about their encounters of water monsters, the lure of magical seals, the lurking of sailors taken by the sea, and, of course, they would tell unforgettable stories about dragons.

I especially loved the stories about dragons, and I believed in their existence right up to the age of eleven.

By that time my family had already moved out of the Irish country to inhabit an English country cottage some miles northwest of Carlisle, on the Scottish border at Kielder Water. It was there that I learned from my uncle that there is no such thing as a dragon, and certainly, dragons did not slumber in the forests surrounding Kielder Water as I had insisted. Doing battle with another dragon no longer seemed possible. The carbuncles I had collected in their cases were broken open, and they were exposed for what they were: valueless stones encased in seashells.

And I guess, too, that was the biggest difference about living in the countryside of Northern Ireland and living in the countryside of northern England. That is, in Northern Ireland I was told stories and they excited me; they did more than excite me, they made everything inside of me live for living. When I used to sit at the piers waiting for the return of the boats, with my oversized head and wide black eyes resting between the wooden rails and my feet dropped over into the water, I noticed the beauty of the fog and rain before I noticed the attempts of art. I lived for the feel of the waves against my legs and I would imagine the pull of their movements to be all the ocean’s currents twisting around my angles in play. In Ireland’s winter along the northern coast, the water is like ice, and I mean just that, cold hard ice that grips your feet with such force and power that you can only helplessly enjoy it, its sharp bite between skin and bone, its curious ability to remind you that you are a living, conscious being and that, without the ability to feel poetry in the moment and without the ability to remember, imaginatively, that very feeling of poetry, then life becomes nothing more than a list of historical facts.

In England, certainly, I still heard wonderful myths and aspiring legends, but they were told to me as if they were wonderful myths and aspiring legends, nothing that directly quickened my heart. Do you see what I mean? Dragons no longer slumbered in the woods nearby, and I knew this before my uncle told me then, like I know it now. But I also knew, like I know now, that though dragons don’t exist, carbuncles do, and their powers of imagination did come from dragons somewhere.

In England, certainly, I still heard wonderful myths and aspiring legends, but they were told to me as if they were wonderful myths and aspiring legends, nothing that directly quickened my heart. Do you see what I mean? Dragons no longer slumbered in the woods nearby, and I knew this before my uncle told me then, like I know it now. But I also knew, like I know now, that though dragons don’t exist, carbuncles do, and their powers of imagination did come from dragons somewhere.And to that end, throughout the forests of Kielder Water, a little boy battled as many as a hundred dragons in a single day.

I can still remember it like it was this afternoon. Perhaps I remember it so well because I’ve forgotten it so well, because, in the short history that is my life, I’ve been able to replace the bare facts of life with something so much more important—memories, the kind of memories that are like lies, but better. They are like lies because no one can remember with perfection, and they so they happen like stories, but they happen in the unseen world of the truth, and they continue to transform with each moment of history. They are no less real or unreal than the facts of life, so that, in spite of what Oscar Wilde writes, there is no need to make distinctions between art, life, and memory. Yes, art lies, and to be good it must abstract from life and history—as Nietzsche writes, history is harmful if it cannot further life—so that life becomes like art rather than art becoming like life. To this day, even after having to attend boarding school in Bristol, then private school in Germany, even after having to learn history, that greatest of inventions from the nineteenth century—that literary urine of knowledge and perception, as it was once described to me—even after reading Borges’ tale of carbuncles and magical beasts for myself, when I write, I write memories from throughout my history, memories which express fleeting sensations of poetry from one moment in history to another moment, which is right now. It is always a short history of my life, and a short history is just that, one that isn’t long. It’s like a glance, a short moment between two blinks. It has no bibliography, no annotation, no corroboration, no listing of primary and secondary sources—it’s anecdotal. It has no guarantee of authenticity. It doesn’t need one—how else could a glance at history weave the multiple threads it has to weave if it is also to have citations and authentications? Corroborated, a simple thing would be equal to three thousand pages and as emptiness as a secret.

Downs - Copyright © 2005

Friday, September 16, 2005

Thursday, September 15, 2005

All We Are Is Light Made Solid - A Day in Paris

10 October 1987

"Simple shapes are inhuman: they fail to resonate with the way nature organizes itself or with the way human perception sees the world."

— George Zebrowsik

8:20am

It is an October morning, still only 7:30, on Rue de la Harpe. I pull back the curtains and open the window (closed for quiet during the night) and a clamor of noise from the street confuses the clean light that slices into my room. It is a market day in the Quarter and just across the way is a miniature Halle or public market, where towering masses of fruits and grains are grouped with painterly effect. The crisp air and the slippery smell of the urban ground, still wet from the morning street cleaners, give substance to the flickering events below. Details, so many details: they are of what experiences are made. And such morning scenes are always thick with them, a tapestry of every color woven in unexpected ways. Yet such chaos is always so instantly coherent to the eye, such complexity is always so tangible to the senses. Even all of those hucksters and small potâger peddlers thronging into the quarter with their chauffeuring wives are given essence by the noisy Babel they produce, one that would last until half past noon, when the market will suddenly quiet down and vanish not unlike how entire eras vanish, rhythmically, leaving just an impression behind.

I arrived in Paris three months ago, after traveling to Perugia and Siena of central Italy, where I was to stay only four nights before returning to Kaiserslautern, Germany. But I was captured by the Tuscan urgency for life, the same raw and unadulterated tactility that persuaded Degas to visit Italy so many times. And eight months later, I finally left Siena for Paris in pursuit of romance. And as in Italy, I found that life here in Paris is too intense to just walk away from it; doing so would be to create a rift between living and merely being alive, and so it has become not so much a matter of wanting to leave this place as it is a matter of being able to conceive of it. Yes, I will be here a long time indeed.

3:18pm

“Bonjour, Monsieur!”

It was my friend Jérôme, who came to ask if I wanted déjeûner. Always Jérôme asked this question, “Veut-il le petit déjeûner ce matin?” He visited me for this purpose and almost no other. I sent down a friendly wave in reply and brought myself down the stairs.

“Ça va, Jérôme?”

“Bien, merci. Aujourd’hui est très beau, non?”

“Oui, est trés beau.”

A good guy Jérôme, a man of over forty and still so curious about the world. He has no small share of the bright intelligence which surprises one among les petit bourgeois, the “little people” or humble class of Paris as they were called. It is a race gift, I think. Unlike people of similar classes in other countries, I venture to hold firm that the French people, especially of Paris, possess a degree of genius unknown to any other nation. I would define it specifically as the veraciousness of common sense.

“How do you say in Italian that the day is nice?” he asked.

“Actually, Italians don’t say that the day is nice,” I explained. “They say ‘Fa bello oggi,’ using the verb fare, which means to make. To say ‘Fa bello’ is actually to say that the day literally makes beauty. You see, even simple utterances in Italian are almost poetic. All of its dialects are this way. To speak is to realize and express the subtle nuances of life. Much like how you Parisians live here in the Quarter, or how French painters like Passarro and Degas used their brushes one-hundred years ago and less.”

Jérôme smiled in acceptance and motioned me in the direction of our favorite pastry shop, Sud Tunisien, just a few minutes walk away.

We turned up Rue de la Harpe, and weaved ourselves into the market on our way towards the river Seine. This was one of the great streets of Paris from Roman times until the last part of the nineteenth century. Though now closed to traffic, Jérôme told me that from its earliest days this street was once an important roadway of the Roman Empire. It wound its serpentine course from the Seine down towards the south of France and that at least fourteen names for it have since been recorded, like the Guitarist and even, says Jérôme, the Old Buckler. It is now called the street of the Harp Player, after King David, but most people around here still refer to it by the name of a favorite café or by the names of their friends who live in one of its apartments. I call it Prégrille, after the French restaurant on the corner. It seems in all of this that Rue de la Harpe is a temporal anomaly, defying time and history much like how light defies form. For me, however, walking down these cobblestones was to walk along thousands of years of human endeavors and aspirations, the blood of history. Either way, perhaps one thing is certain: that we are a moment in astronomic time, a transient of the earth. Only a fool would try to compress a hundred centuries into a few pages of scant conclusions. I proceed.

We visited a street vendor and looked at the various goods. On the table were a display rack of impossible postcards, piles of T-shirt with advertisements, and an array of aluminum-cast Eiffel Towers. Jérôme nodded towards several framed, full-size posters of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist paintings leaning against the tables, works by Monet and Van Gogh mostly. We looked at the Monet’s together.

“And what of Monet, how would you say a man like that lived?” he asked me.

“Hm, with life and vigor, I suppose. I really don’t know. I only know that I see posters of his paintings more so than the other French artists in every gift shop window and touristy vendor like this one.”

“Every area of color is like your utterance of life,” Jérôme explained. “Every subject is fleeting and spontaneous. But look at the details, too,” he whispered. “Little of anything on their own, aren’t they? Yet each one seems like a tiny subject in itself, within the whole subject. In these works, Monet looked at fragments, close-up, and transformed their scale with his large brush and his way of thinking about the canvas, light, form, and color. Details make the picture, but take them away, and they reduce the mood. In themselves they seem insignificant, and when you step back you can see that that is true, that they are not as important in rendering the whole effect as are their actual relationships to one another.”

“I know that he painted quickly, with urgency,” I added, “pursuing the fleeting impression of things.”

“Monet understood a lot of things that modern science has only recently discovered. It was da Vinci before him who wrote that the eye is the chief means whereby the understanding may most fully and abundantly appreciate the world, and Monet certainly took advantage of this precious tool. And as for my part in life,” he laughed and he began our walk again, “I understand only that all our science, measured against reality, is primitive and childlike—and yet it is now the most precise thing we have.

“Chaos,” he announced, and he pointed to a lit candle on the table of another vendor. “It appears to be a very simple system—a wick, the wax—yet it’s inherently unpredictable. The best computer in the world could not predict the pattern this light will take from moment to moment. It’s the secret of the universe.”

“Sounds messy,” I said with a smile.

“Yes,” and he gazed back at the posters. “But what a beautiful mess it can be. It’s what makes the universe so full of possibilities, gives us what free will we have, or at least lets us think that we have it. But tell me, now,” and he hesitated, as if to add drama to what he wanted to ask, “when was the last time you sat to watch the sun rise and felt the spin of the earth?”

“The spin of the earth?”

“Yes, the movement of the planet. It rockets through space at 240.000 kilometers per second. The solar system and the galaxy spin faster than what our best technology can measure. And yet we walk along this street and feel nothing of it. It’s all part of the secret of the universe and this man Monet must have felt it, he must have known it.”

To hear Jérôme talk this way only made my mind wander a moment towards other things, though not far from what he was saying. For instance, I heard rumors that Monet also loved this particular street and that he would often visit it when in the Quarter, especially on those days enshrouded by rain and mist. During his walks I’m told that girls sang from the seventh floor of their apartments at the army men wandering around below and the whole street was an anthill for Parisian students and artists and musicians, all forming a creature of a thousand legs from one end of the course to the other. Looking down at the ground I could only try to imagine the scene for Monet. But the street was miles away from anything I could know so well. The profoundest distances, after all, are never geographical.

“Perhaps he felt gravity,” I tried. “We’re reminded of it daily. But why ask me? It’s you who studies the history of science and painting, not I.”

“Gravity?” Jérôme smirked the kind of smirk that informs others of their obvious idiocy. Having done so, he proceeded to verify his claim.

“At the beginning of this century,” he began, “Rachmaninoff wrote his second symphony and it was powerful. It still is for some people. But today, is there no department store elevator or luxury car commercial that does not use some version of his Symphony No. 2, or his Piano Concerto No. 2, or Tchaikovsky, or Mozart, or Vavaldi? It’s still there, being played in the background, used to sell products, and it adds to the mood, but people are rarely aware of its poetic impact. The thing of it is, when human sensations are replaced by media’s narratives the earth doesn’t need to spin any more. Media exists outside the laws of gravity. Its force lies within the power of the image and its ability to produce some virtual gravity of its own. Look at that there, of Monet’s Water Lilies. There is why I ask you.”

“I don’t see your point.”

“That, I’m afraid, is my point.”

Despite his intelligence Jérôme could be rather confusing, I confess. In most friendships, there is one who is more managing than the other, one who is more outgoing, or more commanding so that, in short, he produces a kind of comfort in a friendship to which even the less dominate person is content. With Jérôme however, if I began to feel the polarity, or if I notice the submissive role in which I am left floundering, he would spontaneously say something that entirely confuses mainly himself and then would proceed to fabricate some fantastic story that only makes him out to be a little neurotic. He is almost uneasy in this way: intimidating, then neurotic. I don’t know which is better.

I should also confess that it was Jérôme who told me the rumor about Monet’s love of this street, which now seems highly suspicious. But one thing I have learned from Jérôme is that what matters in the world is not so much what is true as what is entertaining, at least so long as the truth is unknowable.

We continued up the street, and Jérôme continued to entertain me.

“In Russia, where he was thought to be the next Tchaikovsky, Rachmaninoff was not unlike Monet. He wrote his second symphony in 1907 and by that time Monet had already become obsessed by the water lily motif, having painted many of them, and his Les Grande Décorations was yet to come. During their last decades, both men had similar inspirations. The town of Inånovka, a place of tranquility and family, became synonymous with Rachmaninoff’s later compositions, as was Monet’s garden to his own work. And they were getting older yet becoming more impressive. For Rachmaninoff, though world famous, it was his creative comeback from his poorly received first symphony; and Monet, already famous and wealthy, now faced the issues of blindness and old age with new life. Both were creating symphonies in imaginative designs, packed with expressive melodies, restoring confidence to their careers. I can’t think of a better comparison of two sets of art objects about time, the Waterlilies Suite and Symphony No. 2 in E Minor. Music and painting, even sculpture and literature, were almost merging at that time; but then came the calamities of two world wars, both of which served to splinter the courses of the arts. And now that poster, and all of these advertisements, are the wandering ghosts of Rachmaninoff, Monet and others in a world grown alien to them.”

“Two pieces about time?” I wondered loud.

We reached Sud Tunisien. Before receiving an answer to my question, we bought our breakfasts, which never varied from a sweet role, café au lait, and if available fresh, a handful of grapes. We sat ourselves as always on the street curb just outside the pastry entrance. Jérôme hummed a tune, something French and as clamorous as the market itself. It all fit in however.

“If we wished to make a new world,” he said through his sweet role while looking out into the crowd, “we have the material already. The first one, too, was made out of chaos. That is the character of Monet’s world.”

I just listened.

“I used to think that the moment was a fleeting thing—here in a wink, gone in a wink, with all of its infinite possibilities played out between two instances of nothing, between which laid the experience of life. That’s music. It is something we experience through time, something moving and intoxicating. We find understanding in music from the relationship of its notes, one moment followed by the next, leaving a gap in between them. Then I look at the little water lilies of Monet, or I walk around the huge oval rooms of his Grande Décorations, and I see that, yes, the moment is an instance, just flickers of chaotic light, but it can also eclipse history itself. Monet gives us what is between the musical notes, between one flicker of light and the next. His are not just oil paintings made by a half-blind old man. Each painting is a symphony of light made solid, freeze-framed in a time where there are no seasons and no objects.”

By noon the market was already closing down. The framers loaded their trucks with empty baskets and the vendors urged on the last few potential buyers. So quickly the entire street looked different, even felt different; yet I wandered back to my apartment alone in thought about the entire morning as if I were in the same moment. I thought about Jérôme and I thought about how easily he can create a new way of seeing the world out of insignificant little facts that have big relationships to each other. He’s a lot like Monet, I decide, realizing life as he lived it.

And then I wondered about how this could be done. While looking at buildings and people on Rue de la Harpe I found myself squinting to see the world as impressions of light floating in front of their objects. But it didn’t work, except, when I happened to glance at building No. 33. I suddenly realized it, the secret of the universe. Remember that this street was once called the Old Buckler. Well, I found it; the name, I mean. It is written inside the sculpted stone frame of a doorway. A little thing in itself, I know, but just then I realized that life itself is the movement from the forgotten little things into the unexpected big things, and I believe that that, if nothing else, is certainly true.

Downs - Copyright © 2005

(This post is also on my Travel Journal blog, Pursuing the Esoteric.)

"Simple shapes are inhuman: they fail to resonate with the way nature organizes itself or with the way human perception sees the world."

— George Zebrowsik

8:20am