Tuesday, September 27, 2005

Monday, September 26, 2005

Sketches of What Made the 50's

Albert Einstein’s Spaceman in an Elevator

In 1955 Einstein died without ever finding his man in an elevator. It is a search that may well extend into the next millennium. If a man in an elevator couldn’t feel his own weight in space, Einstein pondered, then what does he feel when the elevator is accelerating through space? Something like weight, but not quite. It has something to do with vibrating superstrings, physicists say. At about the same time as Einstein’s death, the artist Jasper Johns does something interesting. He paints the man in the elevator. Well, okay, not exactly. Actually, Johns started painting images of the American flag, then later he painted images of numbers, and targets, but the idea is the same as Einstein’s elevator man: that it’s just an idea and there it is, gravity or whatever. It doesn’t have any real form.

In 1955 Einstein died without ever finding his man in an elevator. It is a search that may well extend into the next millennium. If a man in an elevator couldn’t feel his own weight in space, Einstein pondered, then what does he feel when the elevator is accelerating through space? Something like weight, but not quite. It has something to do with vibrating superstrings, physicists say. At about the same time as Einstein’s death, the artist Jasper Johns does something interesting. He paints the man in the elevator. Well, okay, not exactly. Actually, Johns started painting images of the American flag, then later he painted images of numbers, and targets, but the idea is the same as Einstein’s elevator man: that it’s just an idea and there it is, gravity or whatever. It doesn’t have any real form.

Hey, Charles Lindbergh Was a Nazi

Sometimes I get sick. The higher I go the more dizzying the view is out of glass elevators. But some people are amazing because they just aren’t bothered by heights. Either they never look out the window to see where they are, or maybe they don’t see anything when they do look. I’m not sure why, but it makes me think of Charles Lindbergh. He’s famous because of this, for flying the Spirit of St. Louis across the Atlantic Ocean, from New York to Paris in 1927. He’s remembered as a daring aviator and an American hero. But people have forgotten, even after WWII, that this hero was a white supremacist and advocator of Nazism. Some people can go higher than others. And when he landed in Paris, it really wasn’t Lindbergh the world cheered for, it was for what he did. That’s always the case, I suppose. So there’s no real form there either. But the other weird thing is that perhaps the most important fact about contemporary times after the Second World War is that they were always going to be different soon. In the 50’s, they could have shot off in any direction. Anyone who could do it flew that plane in some way or another.

Beethoven and Politics

Beethoven was actually afraid of heights. He was the kind of man who would move between five different apartments, each one with a piano in it, shifting every time any one of his friends discovered in which apartment he was staying. For him, music was everything. I mean so much everything that the only thing that stopped him from creating more of it was death. And in his later years, when he composed, he would press his stone-deaf head up against his piano and write music by the feel of its vibrations. It was the reverse of poetry, if you think about it. I mean, if poetry strives toward being music, for Beethoven there was no music, only the poetry of vibrating springs, which I guess gave him music again. Well, whatever it was, it was what he believed in, and this thing he believed in vibrated through his skull. But it wasn’t tangible.

Beethoven was actually afraid of heights. He was the kind of man who would move between five different apartments, each one with a piano in it, shifting every time any one of his friends discovered in which apartment he was staying. For him, music was everything. I mean so much everything that the only thing that stopped him from creating more of it was death. And in his later years, when he composed, he would press his stone-deaf head up against his piano and write music by the feel of its vibrations. It was the reverse of poetry, if you think about it. I mean, if poetry strives toward being music, for Beethoven there was no music, only the poetry of vibrating springs, which I guess gave him music again. Well, whatever it was, it was what he believed in, and this thing he believed in vibrated through his skull. But it wasn’t tangible.

EE Cummings and Death

In about 1950, Cummings wrote this poem:

dying is fine)but Death

?o

baby

i

wouldn’t like

Death if Death

were

good….

because dying is natural….

Death

is strictly

scientific

& artificial &

evil & legal)

We fear death, yet we long for slumber and beautiful dreams. Death is a strange thing. And it is probably the most patient thing, too. As Cummings mentions, excluding what we don’t know about the rest of the universe and existence, dying is natural but death is an exclusively human experience. This is because we know that we will die. And aren’t death and dying clean two different things? Dying, well, we don’t really care about that until it’s accelerated by disease or circumstance. Dying starts at conception, and we call it life. It’s great. But death, that’s the one thing that separates humans from other animals. Since we know we will die, we make a big deal out of it while dying. That’s why we make so much art, have so many religions, make so many artifacts that possess the durability that we just don’t have. And when the H-bomb was tested in ’52, the crowning achievement of men like Einstein looking for men in space elevators, a new idea presented itself: if every human died, then wouldn’t that mean that death would die?

Jackson Pollock and DNA

So you have to envy Pollock in a way. He probably never died, if it was an instant thing, but then again I don’t know the details of his accident. But while he was dying, that is while he was alive, he may have exposed a fundamental contradiction between the legacy of our genes and our experiences in the world. You see, when the structure of DNA was discovered in ’53, biologists thought up another weird idea. Biological bodies were never meant to survive. Only the DNA strings within us all will persist through time. They hold together the information of millions of years of dying. When we die, their code goes on in some other biological body. And superstrings are thought to hold the universe together in the same way too. They call it superstring gravity theory, a cosmic blueprint of everything vibrating in some ambiguous, separate, curved space. Pollock had been painting an ambiguous place, too, and he filled it with seemingly endless calligraphy, making an archeology of time, dripping strings of paint with gravity pulling it down into a layered landscape. Is there a connection?

Hell, I doubt it. But anything could have made sense in the 50’s, in some strange way, if you wanted it to. All those witty ads and Hollywood movies, always looking for something else, even the absurdity of life within the anguish of death—it’s like catching yourself breathe while dead. Right after WWII and into Korea, that was America, left standing to watch the rise of a nuclear age as well as a Cold War. So I suppose anything could make sense in a decade when the most tangible thing in the western world was a man hurdling through space in an elevator. Sure, there were the shutter of an invisible Iron Curtain and the Berlin Wall in ’61, but they aren’t poetry, no matter how much it shook anyone’s skull.

Downs © Copyright 2005

In 1955 Einstein died without ever finding his man in an elevator. It is a search that may well extend into the next millennium. If a man in an elevator couldn’t feel his own weight in space, Einstein pondered, then what does he feel when the elevator is accelerating through space? Something like weight, but not quite. It has something to do with vibrating superstrings, physicists say. At about the same time as Einstein’s death, the artist Jasper Johns does something interesting. He paints the man in the elevator. Well, okay, not exactly. Actually, Johns started painting images of the American flag, then later he painted images of numbers, and targets, but the idea is the same as Einstein’s elevator man: that it’s just an idea and there it is, gravity or whatever. It doesn’t have any real form.

In 1955 Einstein died without ever finding his man in an elevator. It is a search that may well extend into the next millennium. If a man in an elevator couldn’t feel his own weight in space, Einstein pondered, then what does he feel when the elevator is accelerating through space? Something like weight, but not quite. It has something to do with vibrating superstrings, physicists say. At about the same time as Einstein’s death, the artist Jasper Johns does something interesting. He paints the man in the elevator. Well, okay, not exactly. Actually, Johns started painting images of the American flag, then later he painted images of numbers, and targets, but the idea is the same as Einstein’s elevator man: that it’s just an idea and there it is, gravity or whatever. It doesn’t have any real form.Hey, Charles Lindbergh Was a Nazi

Sometimes I get sick. The higher I go the more dizzying the view is out of glass elevators. But some people are amazing because they just aren’t bothered by heights. Either they never look out the window to see where they are, or maybe they don’t see anything when they do look. I’m not sure why, but it makes me think of Charles Lindbergh. He’s famous because of this, for flying the Spirit of St. Louis across the Atlantic Ocean, from New York to Paris in 1927. He’s remembered as a daring aviator and an American hero. But people have forgotten, even after WWII, that this hero was a white supremacist and advocator of Nazism. Some people can go higher than others. And when he landed in Paris, it really wasn’t Lindbergh the world cheered for, it was for what he did. That’s always the case, I suppose. So there’s no real form there either. But the other weird thing is that perhaps the most important fact about contemporary times after the Second World War is that they were always going to be different soon. In the 50’s, they could have shot off in any direction. Anyone who could do it flew that plane in some way or another.

Beethoven and Politics

Beethoven was actually afraid of heights. He was the kind of man who would move between five different apartments, each one with a piano in it, shifting every time any one of his friends discovered in which apartment he was staying. For him, music was everything. I mean so much everything that the only thing that stopped him from creating more of it was death. And in his later years, when he composed, he would press his stone-deaf head up against his piano and write music by the feel of its vibrations. It was the reverse of poetry, if you think about it. I mean, if poetry strives toward being music, for Beethoven there was no music, only the poetry of vibrating springs, which I guess gave him music again. Well, whatever it was, it was what he believed in, and this thing he believed in vibrated through his skull. But it wasn’t tangible.

Beethoven was actually afraid of heights. He was the kind of man who would move between five different apartments, each one with a piano in it, shifting every time any one of his friends discovered in which apartment he was staying. For him, music was everything. I mean so much everything that the only thing that stopped him from creating more of it was death. And in his later years, when he composed, he would press his stone-deaf head up against his piano and write music by the feel of its vibrations. It was the reverse of poetry, if you think about it. I mean, if poetry strives toward being music, for Beethoven there was no music, only the poetry of vibrating springs, which I guess gave him music again. Well, whatever it was, it was what he believed in, and this thing he believed in vibrated through his skull. But it wasn’t tangible.EE Cummings and Death

In about 1950, Cummings wrote this poem:

dying is fine)but Death

?o

baby

i

wouldn’t like

Death if Death

were

good….

because dying is natural….

Death

is strictly

scientific

& artificial &

evil & legal)

We fear death, yet we long for slumber and beautiful dreams. Death is a strange thing. And it is probably the most patient thing, too. As Cummings mentions, excluding what we don’t know about the rest of the universe and existence, dying is natural but death is an exclusively human experience. This is because we know that we will die. And aren’t death and dying clean two different things? Dying, well, we don’t really care about that until it’s accelerated by disease or circumstance. Dying starts at conception, and we call it life. It’s great. But death, that’s the one thing that separates humans from other animals. Since we know we will die, we make a big deal out of it while dying. That’s why we make so much art, have so many religions, make so many artifacts that possess the durability that we just don’t have. And when the H-bomb was tested in ’52, the crowning achievement of men like Einstein looking for men in space elevators, a new idea presented itself: if every human died, then wouldn’t that mean that death would die?

Jackson Pollock and DNA

So you have to envy Pollock in a way. He probably never died, if it was an instant thing, but then again I don’t know the details of his accident. But while he was dying, that is while he was alive, he may have exposed a fundamental contradiction between the legacy of our genes and our experiences in the world. You see, when the structure of DNA was discovered in ’53, biologists thought up another weird idea. Biological bodies were never meant to survive. Only the DNA strings within us all will persist through time. They hold together the information of millions of years of dying. When we die, their code goes on in some other biological body. And superstrings are thought to hold the universe together in the same way too. They call it superstring gravity theory, a cosmic blueprint of everything vibrating in some ambiguous, separate, curved space. Pollock had been painting an ambiguous place, too, and he filled it with seemingly endless calligraphy, making an archeology of time, dripping strings of paint with gravity pulling it down into a layered landscape. Is there a connection?

Hell, I doubt it. But anything could have made sense in the 50’s, in some strange way, if you wanted it to. All those witty ads and Hollywood movies, always looking for something else, even the absurdity of life within the anguish of death—it’s like catching yourself breathe while dead. Right after WWII and into Korea, that was America, left standing to watch the rise of a nuclear age as well as a Cold War. So I suppose anything could make sense in a decade when the most tangible thing in the western world was a man hurdling through space in an elevator. Sure, there were the shutter of an invisible Iron Curtain and the Berlin Wall in ’61, but they aren’t poetry, no matter how much it shook anyone’s skull.

Downs © Copyright 2005

Saturday, September 24, 2005

Thursday, September 22, 2005

Film Critique - Grizzly Man

Werner Herzog's documentary film Grizzly Man explores a fine line between society and nature through an amazing portrait of the late environmentalist, Timothy Treadwell. Treadwell dedicated his life to what he thought was the necessary protection of grizzly bears in the Alaskan wilderness. He spent 13 summers living with the bears, often with surprisingly close interaction, vowing to protect them from poachers. He saw himself as their friend—“the kind warrior”—who stood by their side against the dangers of an encroaching society. But in an ironic twist of fate, in October 2003 Treadwell was devoured by one of the bears that he dedicated his life to protect.

Werner Herzog's documentary film Grizzly Man explores a fine line between society and nature through an amazing portrait of the late environmentalist, Timothy Treadwell. Treadwell dedicated his life to what he thought was the necessary protection of grizzly bears in the Alaskan wilderness. He spent 13 summers living with the bears, often with surprisingly close interaction, vowing to protect them from poachers. He saw himself as their friend—“the kind warrior”—who stood by their side against the dangers of an encroaching society. But in an ironic twist of fate, in October 2003 Treadwell was devoured by one of the bears that he dedicated his life to protect.This is a beautiful film. One is surprised by its calm, especially when one preceives the violent subject matter and the tragic turn of events. But it is not entirely the film’s portrait of Timothy Treadwell that is so engaging and beautiful. What is most captivating is the amazing self-portrait as documented by Treadmill himself.

In his many hours of film, Treadwell captured himself with an honesty and transparency that is rare in even the most candid of documentary filmmaking. He becomes endearingly human. One wants to know him better as he playfully expressions humor, exposing his trouble with women and the world; he does not hide his pain and frustration with nature when a lack of rain and food forces the bears into cannibalism; and he openly shows his confusion, his increasingly bear-like behavior, and his growing hatred towards a society that he feels has rejected him entirely. Through monologues into his camera, we learn of a dark and troubled past, and as he wages an ironic war against human kind, we learn many confessions of an even darker present. Indeed, as the film replays Treadwell’s solitary life in the wild, we watch with eerie proximity the process of a man unfolding.

In my view, this is the absolute best film of the year.

Downs - Copyright © 2005

Monday, September 19, 2005

Film Critique - Broken Flowers

In Broken Flowers Bill Murray plays Don Johnston, an aging “Don Juan” who receives an anonymous letter which tells him that nearly 20 years ago he became a father. His supposed son has left on a mysterious road trip, perhaps to find his father. Murray's neighbor, Winston, takes on the mystery and sends Murray on a cross-country journey through past relationships to discover which one might be the mother of his son.

In Broken Flowers Bill Murray plays Don Johnston, an aging “Don Juan” who receives an anonymous letter which tells him that nearly 20 years ago he became a father. His supposed son has left on a mysterious road trip, perhaps to find his father. Murray's neighbor, Winston, takes on the mystery and sends Murray on a cross-country journey through past relationships to discover which one might be the mother of his son.There is no one who can perform “doing nothing” in the middle of everything better than Bill Murray, and he is able to convey thoughts and emotions with subtleness and purpose. As Murray meets with his former relationships, he approaches them with memories of the past; but, he is quickly confronted with the reality that lives change. It is a reality that is mired with surprises, disappointments, and new sentiments.

Many films explore exactly this interaction between time, memory, and perception. But the film’s director, Jim Barmusch, not only addresses this interplay with sophistication, he is also not afraid to delve deep into the complexity of the pain and confusion that surface with the memories. And it is not without fresh humor and witty turns of phrase. I find this film to be one of the best films of this year.

Downs - Copyright © 2005

Sunday, September 18, 2005

Saturday, September 17, 2005

Dragon Hunts

As a young knight I began each day wearily, overwhelmed by the distance I would have to cross, not knowing what I should expect to find within that distance. And each day, in my mind I fabricated dark corners of the world, hidden niches to seek out, and distant mountains to ascend. I would lose myself within the fantasia of this mental forest, jumping between entangled trees of thought, braving the landscape’s most perilous cliff or cave, becoming lost in a world become labyrinth, a delirium of darkness and shadows, inhabited by dragons of the fiercest kind.

In this world the most glorious of all possessions one could hope to have was that of the carbuncle. A carbuncle was a precious stone, a deep red ruby that is found buried in the brains of dragons. To obtain it, you had to do battle. If not taken fresh from a still living dragon, and in the complete absence of light, the carbuncle would dissolve into thin air. And if you were in possession of a carbuncle, if indeed, you dared to do battle with dragons in the dark, the stone would give you good fortune and everlasting magical power.

The hunt for dragons was always dangerous. The most cunning of warriors, even those who had traveled from the Far East, have been laid to waste by such merciless beasts. For small boys like myself, who were generally known at the time to be virtually invisible to even the keenest sighted dragon, the task was made no easier. Dragons often fed their young the tender meat of seven-year-olds, and unlike small girls and other people, little boys were very tasty. Thus the fact that dragons could not see a little boy meant close to nothing: dragons could still smell their sweet flesh and dragons could still hear their tiny feet like they could hear the breathe of butterflies, even as they slept.

The hunt for dragons was always dangerous. The most cunning of warriors, even those who had traveled from the Far East, have been laid to waste by such merciless beasts. For small boys like myself, who were generally known at the time to be virtually invisible to even the keenest sighted dragon, the task was made no easier. Dragons often fed their young the tender meat of seven-year-olds, and unlike small girls and other people, little boys were very tasty. Thus the fact that dragons could not see a little boy meant close to nothing: dragons could still smell their sweet flesh and dragons could still hear their tiny feet like they could hear the breathe of butterflies, even as they slept.Ambush was feeble. Confrontation was inevitable.

To do hand-to-hand battle with a dragon was the bravest thing you can do. It meant fighting the gnarly and the impossible, gnarly because the battle was always fought in the dark, and impossible because no one else saw the dragon like you saw the dragon. In doing battle with that which is unseen to others, as with doing art that is actually art, the best you can do is interpret the enigmatic; that is, you can only adjust yourself to it. And to interpret the enigmatic is to take a leap into an abyss, a leap from the material into the spiritual. It is awesome, and it is immeasurable.

The removal of a carbuncle was the trickiest of all procedures. First, the conditions had to be prefect if a carbuncle was not to vanish. The smallest intrusion of light, even the faintest flicker of starlight, into the deep regions of the dragon’s brain instantly dissolved the stone. Second, you had to master a remarkable craft. The stone was to be removed while enveloped between two of the dragons scales, both from the very top of its skull, a protective case tightly sewn together with the creature’s own whiskers. And once removed, if removed at all, a carbuncle could continue to exist only if properly kept safe in its case, safe from greed, safe from one’s own vanity, and safe from the disbelieve of others.

You never saw a carbuncle. You believed in it.

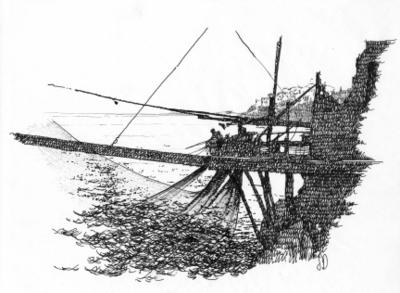

The very first time I heard about carbuncles, I was maybe five. The story was told to me by an old sailor of the Lough Foyle, like so many other stories I heard as a little boy. I’ve always considered this to be one of the most rewarding aspects of my short life history, that is, having grown up as a very young lad in the Northern Irish countryside, just east of Londonderry, and being told tales upon tales by old, bearded seafarers as they worked with their nets at the piers. They would leave early while the morning fog was still breathing, and by evening, if they hadn’t gone as far as Stranraer or even Oban, they would return with the most fantastic and curious stories about their encounters of water monsters, the lure of magical seals, the lurking of sailors taken by the sea, and, of course, they would tell unforgettable stories about dragons.

I especially loved the stories about dragons, and I believed in their existence right up to the age of eleven.

By that time my family had already moved out of the Irish country to inhabit an English country cottage some miles northwest of Carlisle, on the Scottish border at Kielder Water. It was there that I learned from my uncle that there is no such thing as a dragon, and certainly, dragons did not slumber in the forests surrounding Kielder Water as I had insisted. Doing battle with another dragon no longer seemed possible. The carbuncles I had collected in their cases were broken open, and they were exposed for what they were: valueless stones encased in seashells.

And I guess, too, that was the biggest difference about living in the countryside of Northern Ireland and living in the countryside of northern England. That is, in Northern Ireland I was told stories and they excited me; they did more than excite me, they made everything inside of me live for living. When I used to sit at the piers waiting for the return of the boats, with my oversized head and wide black eyes resting between the wooden rails and my feet dropped over into the water, I noticed the beauty of the fog and rain before I noticed the attempts of art. I lived for the feel of the waves against my legs and I would imagine the pull of their movements to be all the ocean’s currents twisting around my angles in play. In Ireland’s winter along the northern coast, the water is like ice, and I mean just that, cold hard ice that grips your feet with such force and power that you can only helplessly enjoy it, its sharp bite between skin and bone, its curious ability to remind you that you are a living, conscious being and that, without the ability to feel poetry in the moment and without the ability to remember, imaginatively, that very feeling of poetry, then life becomes nothing more than a list of historical facts.

In England, certainly, I still heard wonderful myths and aspiring legends, but they were told to me as if they were wonderful myths and aspiring legends, nothing that directly quickened my heart. Do you see what I mean? Dragons no longer slumbered in the woods nearby, and I knew this before my uncle told me then, like I know it now. But I also knew, like I know now, that though dragons don’t exist, carbuncles do, and their powers of imagination did come from dragons somewhere.

In England, certainly, I still heard wonderful myths and aspiring legends, but they were told to me as if they were wonderful myths and aspiring legends, nothing that directly quickened my heart. Do you see what I mean? Dragons no longer slumbered in the woods nearby, and I knew this before my uncle told me then, like I know it now. But I also knew, like I know now, that though dragons don’t exist, carbuncles do, and their powers of imagination did come from dragons somewhere.And to that end, throughout the forests of Kielder Water, a little boy battled as many as a hundred dragons in a single day.

I can still remember it like it was this afternoon. Perhaps I remember it so well because I’ve forgotten it so well, because, in the short history that is my life, I’ve been able to replace the bare facts of life with something so much more important—memories, the kind of memories that are like lies, but better. They are like lies because no one can remember with perfection, and they so they happen like stories, but they happen in the unseen world of the truth, and they continue to transform with each moment of history. They are no less real or unreal than the facts of life, so that, in spite of what Oscar Wilde writes, there is no need to make distinctions between art, life, and memory. Yes, art lies, and to be good it must abstract from life and history—as Nietzsche writes, history is harmful if it cannot further life—so that life becomes like art rather than art becoming like life. To this day, even after having to attend boarding school in Bristol, then private school in Germany, even after having to learn history, that greatest of inventions from the nineteenth century—that literary urine of knowledge and perception, as it was once described to me—even after reading Borges’ tale of carbuncles and magical beasts for myself, when I write, I write memories from throughout my history, memories which express fleeting sensations of poetry from one moment in history to another moment, which is right now. It is always a short history of my life, and a short history is just that, one that isn’t long. It’s like a glance, a short moment between two blinks. It has no bibliography, no annotation, no corroboration, no listing of primary and secondary sources—it’s anecdotal. It has no guarantee of authenticity. It doesn’t need one—how else could a glance at history weave the multiple threads it has to weave if it is also to have citations and authentications? Corroborated, a simple thing would be equal to three thousand pages and as emptiness as a secret.

Downs - Copyright © 2005

Friday, September 16, 2005

Thursday, September 15, 2005

All We Are Is Light Made Solid - A Day in Paris

10 October 1987

"Simple shapes are inhuman: they fail to resonate with the way nature organizes itself or with the way human perception sees the world."

— George Zebrowsik

8:20am

It is an October morning, still only 7:30, on Rue de la Harpe. I pull back the curtains and open the window (closed for quiet during the night) and a clamor of noise from the street confuses the clean light that slices into my room. It is a market day in the Quarter and just across the way is a miniature Halle or public market, where towering masses of fruits and grains are grouped with painterly effect. The crisp air and the slippery smell of the urban ground, still wet from the morning street cleaners, give substance to the flickering events below. Details, so many details: they are of what experiences are made. And such morning scenes are always thick with them, a tapestry of every color woven in unexpected ways. Yet such chaos is always so instantly coherent to the eye, such complexity is always so tangible to the senses. Even all of those hucksters and small potâger peddlers thronging into the quarter with their chauffeuring wives are given essence by the noisy Babel they produce, one that would last until half past noon, when the market will suddenly quiet down and vanish not unlike how entire eras vanish, rhythmically, leaving just an impression behind.

I arrived in Paris three months ago, after traveling to Perugia and Siena of central Italy, where I was to stay only four nights before returning to Kaiserslautern, Germany. But I was captured by the Tuscan urgency for life, the same raw and unadulterated tactility that persuaded Degas to visit Italy so many times. And eight months later, I finally left Siena for Paris in pursuit of romance. And as in Italy, I found that life here in Paris is too intense to just walk away from it; doing so would be to create a rift between living and merely being alive, and so it has become not so much a matter of wanting to leave this place as it is a matter of being able to conceive of it. Yes, I will be here a long time indeed.

3:18pm

“Bonjour, Monsieur!”

It was my friend Jérôme, who came to ask if I wanted déjeûner. Always Jérôme asked this question, “Veut-il le petit déjeûner ce matin?” He visited me for this purpose and almost no other. I sent down a friendly wave in reply and brought myself down the stairs.

“Ça va, Jérôme?”

“Bien, merci. Aujourd’hui est très beau, non?”

“Oui, est trés beau.”

A good guy Jérôme, a man of over forty and still so curious about the world. He has no small share of the bright intelligence which surprises one among les petit bourgeois, the “little people” or humble class of Paris as they were called. It is a race gift, I think. Unlike people of similar classes in other countries, I venture to hold firm that the French people, especially of Paris, possess a degree of genius unknown to any other nation. I would define it specifically as the veraciousness of common sense.

“How do you say in Italian that the day is nice?” he asked.

“Actually, Italians don’t say that the day is nice,” I explained. “They say ‘Fa bello oggi,’ using the verb fare, which means to make. To say ‘Fa bello’ is actually to say that the day literally makes beauty. You see, even simple utterances in Italian are almost poetic. All of its dialects are this way. To speak is to realize and express the subtle nuances of life. Much like how you Parisians live here in the Quarter, or how French painters like Passarro and Degas used their brushes one-hundred years ago and less.”

Jérôme smiled in acceptance and motioned me in the direction of our favorite pastry shop, Sud Tunisien, just a few minutes walk away.

We turned up Rue de la Harpe, and weaved ourselves into the market on our way towards the river Seine. This was one of the great streets of Paris from Roman times until the last part of the nineteenth century. Though now closed to traffic, Jérôme told me that from its earliest days this street was once an important roadway of the Roman Empire. It wound its serpentine course from the Seine down towards the south of France and that at least fourteen names for it have since been recorded, like the Guitarist and even, says Jérôme, the Old Buckler. It is now called the street of the Harp Player, after King David, but most people around here still refer to it by the name of a favorite café or by the names of their friends who live in one of its apartments. I call it Prégrille, after the French restaurant on the corner. It seems in all of this that Rue de la Harpe is a temporal anomaly, defying time and history much like how light defies form. For me, however, walking down these cobblestones was to walk along thousands of years of human endeavors and aspirations, the blood of history. Either way, perhaps one thing is certain: that we are a moment in astronomic time, a transient of the earth. Only a fool would try to compress a hundred centuries into a few pages of scant conclusions. I proceed.

We visited a street vendor and looked at the various goods. On the table were a display rack of impossible postcards, piles of T-shirt with advertisements, and an array of aluminum-cast Eiffel Towers. Jérôme nodded towards several framed, full-size posters of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist paintings leaning against the tables, works by Monet and Van Gogh mostly. We looked at the Monet’s together.

“And what of Monet, how would you say a man like that lived?” he asked me.

“Hm, with life and vigor, I suppose. I really don’t know. I only know that I see posters of his paintings more so than the other French artists in every gift shop window and touristy vendor like this one.”

“Every area of color is like your utterance of life,” Jérôme explained. “Every subject is fleeting and spontaneous. But look at the details, too,” he whispered. “Little of anything on their own, aren’t they? Yet each one seems like a tiny subject in itself, within the whole subject. In these works, Monet looked at fragments, close-up, and transformed their scale with his large brush and his way of thinking about the canvas, light, form, and color. Details make the picture, but take them away, and they reduce the mood. In themselves they seem insignificant, and when you step back you can see that that is true, that they are not as important in rendering the whole effect as are their actual relationships to one another.”

“I know that he painted quickly, with urgency,” I added, “pursuing the fleeting impression of things.”

“Monet understood a lot of things that modern science has only recently discovered. It was da Vinci before him who wrote that the eye is the chief means whereby the understanding may most fully and abundantly appreciate the world, and Monet certainly took advantage of this precious tool. And as for my part in life,” he laughed and he began our walk again, “I understand only that all our science, measured against reality, is primitive and childlike—and yet it is now the most precise thing we have.

“Chaos,” he announced, and he pointed to a lit candle on the table of another vendor. “It appears to be a very simple system—a wick, the wax—yet it’s inherently unpredictable. The best computer in the world could not predict the pattern this light will take from moment to moment. It’s the secret of the universe.”

“Sounds messy,” I said with a smile.

“Yes,” and he gazed back at the posters. “But what a beautiful mess it can be. It’s what makes the universe so full of possibilities, gives us what free will we have, or at least lets us think that we have it. But tell me, now,” and he hesitated, as if to add drama to what he wanted to ask, “when was the last time you sat to watch the sun rise and felt the spin of the earth?”

“The spin of the earth?”

“Yes, the movement of the planet. It rockets through space at 240.000 kilometers per second. The solar system and the galaxy spin faster than what our best technology can measure. And yet we walk along this street and feel nothing of it. It’s all part of the secret of the universe and this man Monet must have felt it, he must have known it.”

To hear Jérôme talk this way only made my mind wander a moment towards other things, though not far from what he was saying. For instance, I heard rumors that Monet also loved this particular street and that he would often visit it when in the Quarter, especially on those days enshrouded by rain and mist. During his walks I’m told that girls sang from the seventh floor of their apartments at the army men wandering around below and the whole street was an anthill for Parisian students and artists and musicians, all forming a creature of a thousand legs from one end of the course to the other. Looking down at the ground I could only try to imagine the scene for Monet. But the street was miles away from anything I could know so well. The profoundest distances, after all, are never geographical.

“Perhaps he felt gravity,” I tried. “We’re reminded of it daily. But why ask me? It’s you who studies the history of science and painting, not I.”

“Gravity?” Jérôme smirked the kind of smirk that informs others of their obvious idiocy. Having done so, he proceeded to verify his claim.

“At the beginning of this century,” he began, “Rachmaninoff wrote his second symphony and it was powerful. It still is for some people. But today, is there no department store elevator or luxury car commercial that does not use some version of his Symphony No. 2, or his Piano Concerto No. 2, or Tchaikovsky, or Mozart, or Vavaldi? It’s still there, being played in the background, used to sell products, and it adds to the mood, but people are rarely aware of its poetic impact. The thing of it is, when human sensations are replaced by media’s narratives the earth doesn’t need to spin any more. Media exists outside the laws of gravity. Its force lies within the power of the image and its ability to produce some virtual gravity of its own. Look at that there, of Monet’s Water Lilies. There is why I ask you.”

“I don’t see your point.”

“That, I’m afraid, is my point.”

Despite his intelligence Jérôme could be rather confusing, I confess. In most friendships, there is one who is more managing than the other, one who is more outgoing, or more commanding so that, in short, he produces a kind of comfort in a friendship to which even the less dominate person is content. With Jérôme however, if I began to feel the polarity, or if I notice the submissive role in which I am left floundering, he would spontaneously say something that entirely confuses mainly himself and then would proceed to fabricate some fantastic story that only makes him out to be a little neurotic. He is almost uneasy in this way: intimidating, then neurotic. I don’t know which is better.

I should also confess that it was Jérôme who told me the rumor about Monet’s love of this street, which now seems highly suspicious. But one thing I have learned from Jérôme is that what matters in the world is not so much what is true as what is entertaining, at least so long as the truth is unknowable.

We continued up the street, and Jérôme continued to entertain me.

“In Russia, where he was thought to be the next Tchaikovsky, Rachmaninoff was not unlike Monet. He wrote his second symphony in 1907 and by that time Monet had already become obsessed by the water lily motif, having painted many of them, and his Les Grande Décorations was yet to come. During their last decades, both men had similar inspirations. The town of Inånovka, a place of tranquility and family, became synonymous with Rachmaninoff’s later compositions, as was Monet’s garden to his own work. And they were getting older yet becoming more impressive. For Rachmaninoff, though world famous, it was his creative comeback from his poorly received first symphony; and Monet, already famous and wealthy, now faced the issues of blindness and old age with new life. Both were creating symphonies in imaginative designs, packed with expressive melodies, restoring confidence to their careers. I can’t think of a better comparison of two sets of art objects about time, the Waterlilies Suite and Symphony No. 2 in E Minor. Music and painting, even sculpture and literature, were almost merging at that time; but then came the calamities of two world wars, both of which served to splinter the courses of the arts. And now that poster, and all of these advertisements, are the wandering ghosts of Rachmaninoff, Monet and others in a world grown alien to them.”

“Two pieces about time?” I wondered loud.

We reached Sud Tunisien. Before receiving an answer to my question, we bought our breakfasts, which never varied from a sweet role, café au lait, and if available fresh, a handful of grapes. We sat ourselves as always on the street curb just outside the pastry entrance. Jérôme hummed a tune, something French and as clamorous as the market itself. It all fit in however.

“If we wished to make a new world,” he said through his sweet role while looking out into the crowd, “we have the material already. The first one, too, was made out of chaos. That is the character of Monet’s world.”

I just listened.

“I used to think that the moment was a fleeting thing—here in a wink, gone in a wink, with all of its infinite possibilities played out between two instances of nothing, between which laid the experience of life. That’s music. It is something we experience through time, something moving and intoxicating. We find understanding in music from the relationship of its notes, one moment followed by the next, leaving a gap in between them. Then I look at the little water lilies of Monet, or I walk around the huge oval rooms of his Grande Décorations, and I see that, yes, the moment is an instance, just flickers of chaotic light, but it can also eclipse history itself. Monet gives us what is between the musical notes, between one flicker of light and the next. His are not just oil paintings made by a half-blind old man. Each painting is a symphony of light made solid, freeze-framed in a time where there are no seasons and no objects.”

By noon the market was already closing down. The framers loaded their trucks with empty baskets and the vendors urged on the last few potential buyers. So quickly the entire street looked different, even felt different; yet I wandered back to my apartment alone in thought about the entire morning as if I were in the same moment. I thought about Jérôme and I thought about how easily he can create a new way of seeing the world out of insignificant little facts that have big relationships to each other. He’s a lot like Monet, I decide, realizing life as he lived it.

And then I wondered about how this could be done. While looking at buildings and people on Rue de la Harpe I found myself squinting to see the world as impressions of light floating in front of their objects. But it didn’t work, except, when I happened to glance at building No. 33. I suddenly realized it, the secret of the universe. Remember that this street was once called the Old Buckler. Well, I found it; the name, I mean. It is written inside the sculpted stone frame of a doorway. A little thing in itself, I know, but just then I realized that life itself is the movement from the forgotten little things into the unexpected big things, and I believe that that, if nothing else, is certainly true.

Downs - Copyright © 2005

(This post is also on my Travel Journal blog, Pursuing the Esoteric.)

"Simple shapes are inhuman: they fail to resonate with the way nature organizes itself or with the way human perception sees the world."

— George Zebrowsik

8:20am

It is an October morning, still only 7:30, on Rue de la Harpe. I pull back the curtains and open the window (closed for quiet during the night) and a clamor of noise from the street confuses the clean light that slices into my room. It is a market day in the Quarter and just across the way is a miniature Halle or public market, where towering masses of fruits and grains are grouped with painterly effect. The crisp air and the slippery smell of the urban ground, still wet from the morning street cleaners, give substance to the flickering events below. Details, so many details: they are of what experiences are made. And such morning scenes are always thick with them, a tapestry of every color woven in unexpected ways. Yet such chaos is always so instantly coherent to the eye, such complexity is always so tangible to the senses. Even all of those hucksters and small potâger peddlers thronging into the quarter with their chauffeuring wives are given essence by the noisy Babel they produce, one that would last until half past noon, when the market will suddenly quiet down and vanish not unlike how entire eras vanish, rhythmically, leaving just an impression behind.

I arrived in Paris three months ago, after traveling to Perugia and Siena of central Italy, where I was to stay only four nights before returning to Kaiserslautern, Germany. But I was captured by the Tuscan urgency for life, the same raw and unadulterated tactility that persuaded Degas to visit Italy so many times. And eight months later, I finally left Siena for Paris in pursuit of romance. And as in Italy, I found that life here in Paris is too intense to just walk away from it; doing so would be to create a rift between living and merely being alive, and so it has become not so much a matter of wanting to leave this place as it is a matter of being able to conceive of it. Yes, I will be here a long time indeed.

3:18pm

“Bonjour, Monsieur!”

It was my friend Jérôme, who came to ask if I wanted déjeûner. Always Jérôme asked this question, “Veut-il le petit déjeûner ce matin?” He visited me for this purpose and almost no other. I sent down a friendly wave in reply and brought myself down the stairs.

“Ça va, Jérôme?”

“Bien, merci. Aujourd’hui est très beau, non?”

“Oui, est trés beau.”

A good guy Jérôme, a man of over forty and still so curious about the world. He has no small share of the bright intelligence which surprises one among les petit bourgeois, the “little people” or humble class of Paris as they were called. It is a race gift, I think. Unlike people of similar classes in other countries, I venture to hold firm that the French people, especially of Paris, possess a degree of genius unknown to any other nation. I would define it specifically as the veraciousness of common sense.

“How do you say in Italian that the day is nice?” he asked.

“Actually, Italians don’t say that the day is nice,” I explained. “They say ‘Fa bello oggi,’ using the verb fare, which means to make. To say ‘Fa bello’ is actually to say that the day literally makes beauty. You see, even simple utterances in Italian are almost poetic. All of its dialects are this way. To speak is to realize and express the subtle nuances of life. Much like how you Parisians live here in the Quarter, or how French painters like Passarro and Degas used their brushes one-hundred years ago and less.”

Jérôme smiled in acceptance and motioned me in the direction of our favorite pastry shop, Sud Tunisien, just a few minutes walk away.

We turned up Rue de la Harpe, and weaved ourselves into the market on our way towards the river Seine. This was one of the great streets of Paris from Roman times until the last part of the nineteenth century. Though now closed to traffic, Jérôme told me that from its earliest days this street was once an important roadway of the Roman Empire. It wound its serpentine course from the Seine down towards the south of France and that at least fourteen names for it have since been recorded, like the Guitarist and even, says Jérôme, the Old Buckler. It is now called the street of the Harp Player, after King David, but most people around here still refer to it by the name of a favorite café or by the names of their friends who live in one of its apartments. I call it Prégrille, after the French restaurant on the corner. It seems in all of this that Rue de la Harpe is a temporal anomaly, defying time and history much like how light defies form. For me, however, walking down these cobblestones was to walk along thousands of years of human endeavors and aspirations, the blood of history. Either way, perhaps one thing is certain: that we are a moment in astronomic time, a transient of the earth. Only a fool would try to compress a hundred centuries into a few pages of scant conclusions. I proceed.

We visited a street vendor and looked at the various goods. On the table were a display rack of impossible postcards, piles of T-shirt with advertisements, and an array of aluminum-cast Eiffel Towers. Jérôme nodded towards several framed, full-size posters of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist paintings leaning against the tables, works by Monet and Van Gogh mostly. We looked at the Monet’s together.

“And what of Monet, how would you say a man like that lived?” he asked me.

“Hm, with life and vigor, I suppose. I really don’t know. I only know that I see posters of his paintings more so than the other French artists in every gift shop window and touristy vendor like this one.”

“Every area of color is like your utterance of life,” Jérôme explained. “Every subject is fleeting and spontaneous. But look at the details, too,” he whispered. “Little of anything on their own, aren’t they? Yet each one seems like a tiny subject in itself, within the whole subject. In these works, Monet looked at fragments, close-up, and transformed their scale with his large brush and his way of thinking about the canvas, light, form, and color. Details make the picture, but take them away, and they reduce the mood. In themselves they seem insignificant, and when you step back you can see that that is true, that they are not as important in rendering the whole effect as are their actual relationships to one another.”

“I know that he painted quickly, with urgency,” I added, “pursuing the fleeting impression of things.”

“Monet understood a lot of things that modern science has only recently discovered. It was da Vinci before him who wrote that the eye is the chief means whereby the understanding may most fully and abundantly appreciate the world, and Monet certainly took advantage of this precious tool. And as for my part in life,” he laughed and he began our walk again, “I understand only that all our science, measured against reality, is primitive and childlike—and yet it is now the most precise thing we have.

“Chaos,” he announced, and he pointed to a lit candle on the table of another vendor. “It appears to be a very simple system—a wick, the wax—yet it’s inherently unpredictable. The best computer in the world could not predict the pattern this light will take from moment to moment. It’s the secret of the universe.”

“Sounds messy,” I said with a smile.

“Yes,” and he gazed back at the posters. “But what a beautiful mess it can be. It’s what makes the universe so full of possibilities, gives us what free will we have, or at least lets us think that we have it. But tell me, now,” and he hesitated, as if to add drama to what he wanted to ask, “when was the last time you sat to watch the sun rise and felt the spin of the earth?”

“The spin of the earth?”

“Yes, the movement of the planet. It rockets through space at 240.000 kilometers per second. The solar system and the galaxy spin faster than what our best technology can measure. And yet we walk along this street and feel nothing of it. It’s all part of the secret of the universe and this man Monet must have felt it, he must have known it.”

To hear Jérôme talk this way only made my mind wander a moment towards other things, though not far from what he was saying. For instance, I heard rumors that Monet also loved this particular street and that he would often visit it when in the Quarter, especially on those days enshrouded by rain and mist. During his walks I’m told that girls sang from the seventh floor of their apartments at the army men wandering around below and the whole street was an anthill for Parisian students and artists and musicians, all forming a creature of a thousand legs from one end of the course to the other. Looking down at the ground I could only try to imagine the scene for Monet. But the street was miles away from anything I could know so well. The profoundest distances, after all, are never geographical.

“Perhaps he felt gravity,” I tried. “We’re reminded of it daily. But why ask me? It’s you who studies the history of science and painting, not I.”

“Gravity?” Jérôme smirked the kind of smirk that informs others of their obvious idiocy. Having done so, he proceeded to verify his claim.

“At the beginning of this century,” he began, “Rachmaninoff wrote his second symphony and it was powerful. It still is for some people. But today, is there no department store elevator or luxury car commercial that does not use some version of his Symphony No. 2, or his Piano Concerto No. 2, or Tchaikovsky, or Mozart, or Vavaldi? It’s still there, being played in the background, used to sell products, and it adds to the mood, but people are rarely aware of its poetic impact. The thing of it is, when human sensations are replaced by media’s narratives the earth doesn’t need to spin any more. Media exists outside the laws of gravity. Its force lies within the power of the image and its ability to produce some virtual gravity of its own. Look at that there, of Monet’s Water Lilies. There is why I ask you.”

“I don’t see your point.”

“That, I’m afraid, is my point.”

Despite his intelligence Jérôme could be rather confusing, I confess. In most friendships, there is one who is more managing than the other, one who is more outgoing, or more commanding so that, in short, he produces a kind of comfort in a friendship to which even the less dominate person is content. With Jérôme however, if I began to feel the polarity, or if I notice the submissive role in which I am left floundering, he would spontaneously say something that entirely confuses mainly himself and then would proceed to fabricate some fantastic story that only makes him out to be a little neurotic. He is almost uneasy in this way: intimidating, then neurotic. I don’t know which is better.

I should also confess that it was Jérôme who told me the rumor about Monet’s love of this street, which now seems highly suspicious. But one thing I have learned from Jérôme is that what matters in the world is not so much what is true as what is entertaining, at least so long as the truth is unknowable.

We continued up the street, and Jérôme continued to entertain me.

“In Russia, where he was thought to be the next Tchaikovsky, Rachmaninoff was not unlike Monet. He wrote his second symphony in 1907 and by that time Monet had already become obsessed by the water lily motif, having painted many of them, and his Les Grande Décorations was yet to come. During their last decades, both men had similar inspirations. The town of Inånovka, a place of tranquility and family, became synonymous with Rachmaninoff’s later compositions, as was Monet’s garden to his own work. And they were getting older yet becoming more impressive. For Rachmaninoff, though world famous, it was his creative comeback from his poorly received first symphony; and Monet, already famous and wealthy, now faced the issues of blindness and old age with new life. Both were creating symphonies in imaginative designs, packed with expressive melodies, restoring confidence to their careers. I can’t think of a better comparison of two sets of art objects about time, the Waterlilies Suite and Symphony No. 2 in E Minor. Music and painting, even sculpture and literature, were almost merging at that time; but then came the calamities of two world wars, both of which served to splinter the courses of the arts. And now that poster, and all of these advertisements, are the wandering ghosts of Rachmaninoff, Monet and others in a world grown alien to them.”

“Two pieces about time?” I wondered loud.

We reached Sud Tunisien. Before receiving an answer to my question, we bought our breakfasts, which never varied from a sweet role, café au lait, and if available fresh, a handful of grapes. We sat ourselves as always on the street curb just outside the pastry entrance. Jérôme hummed a tune, something French and as clamorous as the market itself. It all fit in however.

“If we wished to make a new world,” he said through his sweet role while looking out into the crowd, “we have the material already. The first one, too, was made out of chaos. That is the character of Monet’s world.”

I just listened.

“I used to think that the moment was a fleeting thing—here in a wink, gone in a wink, with all of its infinite possibilities played out between two instances of nothing, between which laid the experience of life. That’s music. It is something we experience through time, something moving and intoxicating. We find understanding in music from the relationship of its notes, one moment followed by the next, leaving a gap in between them. Then I look at the little water lilies of Monet, or I walk around the huge oval rooms of his Grande Décorations, and I see that, yes, the moment is an instance, just flickers of chaotic light, but it can also eclipse history itself. Monet gives us what is between the musical notes, between one flicker of light and the next. His are not just oil paintings made by a half-blind old man. Each painting is a symphony of light made solid, freeze-framed in a time where there are no seasons and no objects.”

By noon the market was already closing down. The framers loaded their trucks with empty baskets and the vendors urged on the last few potential buyers. So quickly the entire street looked different, even felt different; yet I wandered back to my apartment alone in thought about the entire morning as if I were in the same moment. I thought about Jérôme and I thought about how easily he can create a new way of seeing the world out of insignificant little facts that have big relationships to each other. He’s a lot like Monet, I decide, realizing life as he lived it.

And then I wondered about how this could be done. While looking at buildings and people on Rue de la Harpe I found myself squinting to see the world as impressions of light floating in front of their objects. But it didn’t work, except, when I happened to glance at building No. 33. I suddenly realized it, the secret of the universe. Remember that this street was once called the Old Buckler. Well, I found it; the name, I mean. It is written inside the sculpted stone frame of a doorway. A little thing in itself, I know, but just then I realized that life itself is the movement from the forgotten little things into the unexpected big things, and I believe that that, if nothing else, is certainly true.

Downs - Copyright © 2005

(This post is also on my Travel Journal blog, Pursuing the Esoteric.)

Monday, September 12, 2005

Saturday, September 10, 2005

A Walk With Antoni Gaudi

October 1995

As a child Antoni Gaudi i Cornet had incurred a type of rheumatism that never left him. To combat this weakness, he adopted a pattern of behavior that involved, among other rituals, a careful vegetarian diet, homeopathic drugs, a variety of bathing procedures, and regular hiking. It was a pattern of behavior that was bound to set him apart. As thus, after he moved to Parc Guell in 1906, Gaudi left his new residence at the southeastern side of the park seven days a week, for 20 years, to hike 4 and a half kilometers to his work at the Sagrada Familia.

As a child Antoni Gaudi i Cornet had incurred a type of rheumatism that never left him. To combat this weakness, he adopted a pattern of behavior that involved, among other rituals, a careful vegetarian diet, homeopathic drugs, a variety of bathing procedures, and regular hiking. It was a pattern of behavior that was bound to set him apart. As thus, after he moved to Parc Guell in 1906, Gaudi left his new residence at the southeastern side of the park seven days a week, for 20 years, to hike 4 and a half kilometers to his work at the Sagrada Familia.

The hikes began at about 7 in the morning. Gaudi’s usual hiking partner was Lorenzo Matamala, a local sculptor and life-long friend. They would walk together in both directions, to and from the church, but during the year of 1906, despite his own fragility, Guadi found himself walking alone.

This morning, it is nearly 7:30, and I am sitting on the pathway that leads from his old house in the park to the streets of Barcelona. I will trace his path from this house to his still unfinished masterpiece, the Church of the Sagrda Familia, a path that one day lead to his death.

Walking alone did not seem to bother him. By that time he had become accustom to isolation. In fact, he was so consistent with his hikes that in the morning the owners of the small hotel, situated just across the entrance of the park, could expect to see the same baggy black suited man stroll onto Carrer de Milans from this path that lead from behind the wall of the park. He was like reliable clockwork.

From his door he would walk straight and followed his walkway to a bridge. It took a moment. From the bridge he could see the entire southern half of the park, and it was at this position above the city of Barcelona that Gaudi like to be when reflecting on life and on himself. And there was no better place for it—not only because Parc Guell was his home at the time, but also because it was a place of his own thought and design. Gaudi designed this park. It was his first mature work as an architect.

He designed it 1903. The years that lead up to his last walk were important years of consolidation for Gaudi. It was a time when he moved towards a greater expression of freedom. He was fully aware that no one would follow where he was about to go.

Originally, the park was to be a high-income housing project with a grand entrance, grand lodges, a grand plaza, and grand carriage roads. These ideas were conceived by Gaudi’s main patron, Eusebi Guell i Bacigalupi, a 19th century Catalunian mercantile knight with elaborate tastes and an elaborate reputation to assert.

Though most of the basic construction of the park had been completed by 1906, it was obvious to Gaudi that the project would never fully develop. Only 2 buyers signed up and built homes. The lost, over sixty of them, were too expensive and the site was too far away from the city for most people. Only those who wished, and could afford, to escape to a more natural setting would build at Parc Guell, and of those where were few.

Besides this, Gaudi was simply in conflict with his society. His name was known as the famous architect of the Sagrada Familia, he was out of sync with the modernisme movement of the time. And few knew his face.

Besides this, Gaudi was simply in conflict with his society. His name was known as the famous architect of the Sagrada Familia, he was out of sync with the modernisme movement of the time. And few knew his face.

For Gaudi the park was a statement about his deep belief in Catalunian nationalism, a dominant sense of existence for many Barcelonese during the first quarter of the 20th century, and it served as the background for the design of the park. But it was not this that put him out of his society, for it responded to a mass of ideals that were dear to the hearts of all Catalunians. Rather, it was the way in which the symbols and metaphors alluding to Catalunya were carried out in his work.

For example, when Gaudi left this bridge, he would follow a stone path down to the right of two entrance pavilions. Each one is an architectural reenactment of the two house in the story of Hansel und Gretel.* The left-hand house is the house of the children and the other is that of the wicked witch. Gaudi particularly liked the latter one because of the mushroom roof. “That marvelous ceramic fong,” he might have told himself while walking by, “Amanita muscaria--poisonous, hallucinogenic, and distasteful: what is a better emblem for a sorceress?”

The house of Hansel and Gretel, or Ton i Guida in senor Gaudi’s Catalunian, is crowned with a cross and ornamented with blue and white checkers, the colors of the Bavarian flag. It stands tall as a symbol of virtue.

The house of Hansel and Gretel, or Ton i Guida in senor Gaudi’s Catalunian, is crowned with a cross and ornamented with blue and white checkers, the colors of the Bavarian flag. It stands tall as a symbol of virtue.

And between the house of the good and the house of the bad stretches a gate cast in iron through which one begins one’s journey to the forest of the park. (Though in 1906, there was no forest. The land on which the park was constructed, originally two farms on a shallow hill, was still quite desolate of vegetation.)

Nevertheless, it took great courage, or just great personal belief, to deign something so ostentatious for such a serious and ambitious project.

I don’t think the failure of this park mattered much to Gaudi. Yes, it was rather ugly at the time. It’s still a little hard on the nerves now. But I think what really mattered to Gaudi was the freedom of expression given to him. He took full advantage of that opportunity. This is especially true in the use of fragments of tile.

And “what a weird sight,” one writer wrote in a 1905 satirical weekly of the construction sight of the church. “Thirty men braking tiles and still thirty more recombining the fragments again as pieces of decoration. Hanged if can understand it!”

And “what a weird sight,” one writer wrote in a 1905 satirical weekly of the construction sight of the church. “Thirty men braking tiles and still thirty more recombining the fragments again as pieces of decoration. Hanged if can understand it!”

At the time, the park was a freak place. But Gaudi was fully aware of historical situation. He was fully aware that in time his work would have positive force, just by the fact that it was in conflict with his time. Decades later, I might add, Dadaists and Cubists were also making collages.

At the time, the park was a freak place. But Gaudi was fully aware of historical situation. He was fully aware that in time his work would have positive force, just by the fact that it was in conflict with his time. Decades later, I might add, Dadaists and Cubists were also making collages.

It is important, too, to say something of Gaudi the man before he designed Parc Guell. This would help to give a clearer understanding of his increased sense of self-comfort and unity from about the year 1888 to his death in 1926, a feeling of ease with his work and his time which ironically only increased his isolation.

For this we must trace his route out of the park and long the dirt streets of an old Barcelona. Just a little further from the empty gate houses of the park on Carrer de Milans, I head west, then I turned south down Passeig Sant Jose de la Muntanya until it meets Trasvessera de Dalt. Just a block west from the corner, in a hinge of an L-shaped street called calle de las Carolinas, is one of Gaudi’s first commissions.

For this we must trace his route out of the park and long the dirt streets of an old Barcelona. Just a little further from the empty gate houses of the park on Carrer de Milans, I head west, then I turned south down Passeig Sant Jose de la Muntanya until it meets Trasvessera de Dalt. Just a block west from the corner, in a hinge of an L-shaped street called calle de las Carolinas, is one of Gaudi’s first commissions.

The Casa Vicens, I will say only briefly, is an excellent example of the younger Gaudi. It is busy with ornament and witty little touches, like the little iron dragons on its window grilles. It stands as an expression of industry, covered with floral ceramics and tile, because, after all, his patron was a tile manufacture.

And the younger Gaudi, well he was something of a dandy, or at least thought he could be. Amazingly shy, he was vain about his appearance. He loved the theater, the opera, the ballet, and he loved rich patrons. He even once wrote a letter to a patron to down an offer to design a textile factory, not because Gaudi disliked the work but because there was no money in it. Gaudi wrote to his patron in Madrid: “As you can surely appreciate I live by my work and I cannot dedicate myself to vague or experimental projects—I believe that you yourself would never give up a sure thing for an unsure one.”

In 1878, virtually fresh out of architectural school, the Casa Vicens was a sure thing. And Manuel Vicens i Montaner was a rich textile producer—that is until after he received the bill for the home he had built by Gaudi. It nearly bankrupted him, but not in a literal sense, of course. And that was the case for most of Gaudi’s patrons, especially Guell. Yet, to them the cost was always insignificant to the boldness and showiness of their new homes.

Similar work during the time—other lavish town houses and elaborate apartment complexes, all for rich dwellers—are certainly in marked contrast to the work that followed. But it should be noted that the metamorphosis of Gaudi the dandy into Gaudi the modest and humble architect of the Sagrada Familia was gradual. In the 1880’s Barcelona enjoyed an economic prosperity which allowed the development of the city. Modernisme was the prevailing fashionable style. Gaudi grew to dislike it, though it could be argued that he had a part in its creation, and then moved on.

It was around then that he began to accept second-hand work begun by his colleagues. It takes a great deal of humility, and very little pride, to finish work others felt fit to abandon.

In 1886, the economic boom collapsed, but the energy of Modernisme lasted, as far as I cam tell, until about 1905. It stood for diffusion, and everything was vague. Guadi stood for unity, staying ahead of this time. By 1883, when he accepted the task of continuing the work of building the Holy Temple of the Sagrada Familia, there seemed to have been a synthesis in Gaudi’s spiritually. He was 31 then, and he continued developing along the lines that he had been following up this point, that is ostentatiousness, but there is also that one important aspect I’ve been alluding to here.

On the 3rd of November, 1883, Gaudi had a spiritual experience which, as far as anyone seems to know, he never clearly described. The experience convinced him that a miracle of St. Joseph had brought to him the commission to complete the church of the Sagrada Familia. His religious zeal steadily grew from there, and evening in the secular Par Guell, his statement of Catalunya’s nationalism, he managed to pull religious significance into its design.

In this case, among other examples within the park, the Bavarian houses relate to Bavaria’s Richard Wagner, the composer who knew Engelbert Humperdinck and who wrote the Barcelona hit opera in 1900 titled, of course, Ton i Guida. Together these men collaborated on Parsifal, an opera which set the location of the Holy Grail in no other place than Catalunya. So, what better place and reason for Catholic Cataunians, or anyone in Gaudi’s no religious eyes, to unite?

His increased tendency towards isolation dates from the 3-year period, starting in 1900. He was still a sociable man, but nevertheless he often withdrew into silent work. For example, at this time he frequently hid himself anyway to work on the Temple of the Sagrda Familia, to which I am still walking.

From the corner on Travessera de Dalt, Gaudi would go east several blocks and then turn south, down Carrer de Sardenya. This long stretch leads directly to the temple.

A bookseller started the monumental project. Jose Maria Bocabella wanted to “bring about…the triumph of the Catholic Church” to those who were godless. Sometime around 1874, Bocabella came up with the idea of constructing the church that was to be offered as an expiatory sacrifice for the sins of Barcelona. It was to be built entirely on the proceeds of alms. And, it was to be an exact copy of the Basilica at Loreto, in Italy. To complete this task, he asked for the services of Francisco del Villar.

Because of financial reasons (I think), the site for the church was changed from within the city to the outskirts. Del Villar drew up plans for the neo-Gothic church and in March of 1882 the ground breaking took place. In November of 1883, Villar quit. I have been able to find anything in my research about the conditions under which he left the job, and under want conditions, aside from a vague spiritual experience, Gaudi accepted it.

What urged Gaudi in the Sagrada Familia, it seems to me, was the freedom offered to him. From the moment the Josephines hired Gaudi to complete the temple, he had a free hand. Nobody interfered with his plans or offered any criticism of them. He more ostentatious it got, the better. Yet, for over 19 years, as the temple grew in an as yet isolated area of the city, and despite the numerous published articles at the time, Gaudi’s involvement with the temple was surprisingly anonymous.

The Sagrda Familia did not appeal to the tastes of ideas of the time. By 1906, however, the culture of the city had changed. Art Nouveau extravaganzas were being dominated by a movement towards traditional images of the Mediterranean. The temple became synonymous with Gaudi. He was a popular hero, in demand all over the city by anyone who could appreciate the work of an apparently isolated spirit.

And why not? After all, he was the genius who could unit faith and art. And the irony is interesting. Before 1906, a little know architect tried to catch the eye of the entire city. Then for 19 years he developed a sense of security within himself, abandoning materialism to build “a vessel to gather in the godless.” And by that year, when he had full command of the cities most popular and important project, and the status of a hero, he wanted little else than to be left alone, to express his intense desire for life, particularly religious life, and his structural genius.

For Gaudi, the temple was not an exercise in beauty or architecture. It was an attempt to encrust life in stone.

Since the project was to be constructed entirely from donations, as Gaudi made his walks he never stopped begging for money. All long this street, he knocked on doors and asked for any amount the poor could give. And from the rich, he expected a significant sacrifice. It is not surprising, then, that Barceloneses would quickly cross the street when they saw the old genius headed their way.

“Make a sacrifice!” he would say, with a thousand-yard stare from his blue eyes.

“With pleasure,” the donor my say, “It’s no sacrifice at all.”

“Then give enough for it to be a sacrifice! Charity that does not amount to sacrifice is not charity at all. Often, it’s merely vanity.”

And just across the street from the temple, at the corner of Carrer de Sardenya and Carrer del Provena, Gaudi would approach the site with his morning earnings and any bottles or broken pieces of tile found on the way. Except, one day in 1926, he never made it to the temple. He was fatally struck by a street car.

For three days Gaudi laid in a morgue, unidentified. The hero of his city was unknown.

In that year, Gaudi would have seen the Façade of the Nativity, just begun and not yet reached the rose window. The bud of one of the spires, though small, was still a monumental sight. The entire temple was surrounded by barren fields full of black goats.

The Sagrada Familia was Gaudi’s last project, and it was perhaps his most cared for personal struggles to finish. He knew that he would never live to see it completed, but, as with isolation, that idea did not bother him. He was comfortable; and in a sense, the Sagrada Familia remains as his last expression of the struggle to unify a society that noticed him, and his deep urgency for life, too late.

Downs © Copyright 2005

(This post is also on my Travel Journal blog, Pursuing the Esoteric.)

As a child Antoni Gaudi i Cornet had incurred a type of rheumatism that never left him. To combat this weakness, he adopted a pattern of behavior that involved, among other rituals, a careful vegetarian diet, homeopathic drugs, a variety of bathing procedures, and regular hiking. It was a pattern of behavior that was bound to set him apart. As thus, after he moved to Parc Guell in 1906, Gaudi left his new residence at the southeastern side of the park seven days a week, for 20 years, to hike 4 and a half kilometers to his work at the Sagrada Familia.