Monday, October 24, 2005

Saturday, October 22, 2005

The Nature of Maps

“Nothing is definable, unless it has no history.” — Nietzsche

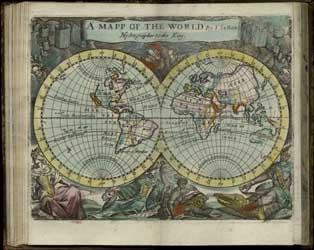

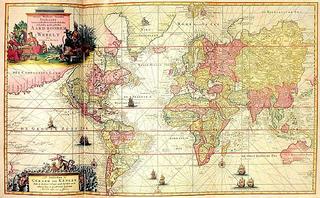

I love maps. I am interested in them because they embody many of the things I like. Maps are cultural artifacts comparable to diaries, art objects, literature, or musical instruments. Almost every culture had developed maps, but they did it with enormously varying degrees of sophistication. The origin of maps seems instinctive, in that they are products both of the intellect and the imagination confronting problems in reality. That is, in the quest to describe reality, maps tell stories. They help construct a history in which they are a part. I like all of these things, especially stories.

I love maps. I am interested in them because they embody many of the things I like. Maps are cultural artifacts comparable to diaries, art objects, literature, or musical instruments. Almost every culture had developed maps, but they did it with enormously varying degrees of sophistication. The origin of maps seems instinctive, in that they are products both of the intellect and the imagination confronting problems in reality. That is, in the quest to describe reality, maps tell stories. They help construct a history in which they are a part. I like all of these things, especially stories.

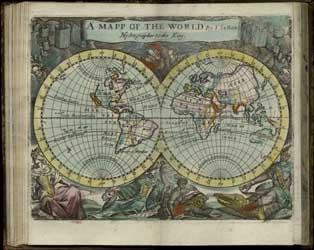

It is self-evident that the only true and accurate map of the world is a three-dimensional one. Yet, mapmakers have persistently striven to re-create the world on paper. Why? Is it simply because of the portability of a roll of parchment or vellum? Or, is it also the desire to see an image of the earth focused before us, clear, self-contained, comprehensible, and masterable? The paradox of this question is distilled within the cartographic language itself. The task, then, is to describe and interpret that language.

This essay explores the ontological nature of maps in two short parts. Part One, Believing is Seeing, focuses a medieval example of how people influence what maps show. In Part Two, Seeing is Believing, a map described by Herodotus from ancient Greek history shows how iconography can influence the behavior of people. In both cases, we see that maps help to construct a history, serve our interests, render visible that which is invisible, and interestingly, maps lie to us.

PART ONE - Believing is Seeing

The legend of Prestor John, a powerful Christian priest-king of unimaginable wealth and power, began in the 1030's, just before the start of the Great Crusades. This timing is not a coincidence. Maps that showed the kingdom of Prestor John contributed to the compulsory drive of the Crusades. And by the 12th century such maps clearly show a fictitious empire describe as belonging to Prestor John. These maps, however, show lands that had not yet been explored by western cartographers. They were, in fact, often completely imaginary.

In a lengthy letter supposedly written by the great monarch himself and sent to Emperor Manuel Commenus of Byzantine, Prestor John says, “…believe without doubting that I, Presbyter Ioannes, who reign[s] supreme, exceed[s] in riches, virtue, and power [over] all creatures who dwell under heaven … am a devout Christian and everywhere protect the Christians of our empire.”

The empire of Prestor John was a wondrous place which stretched from “the valley of deserted Babylon close by the Tower of Babel” to include “the Three Indias”. “Honey flows in our land, and milk everywhere abounds … In one of our territories no poison can do harm.” The river Physon, which “emerges[s] from Paradise”, is pebbled with diamonds, emeralds, and “many other precious stones.” There is even “a sandy sea without water. For the sand moves and swells into waves like the sea and is never still.” 1

To the medieval mind such a Christian ruler of immense riches and power would have made an ideal ally. For they feared the armies of Gog and Magog “shalt come from thy place out of the north parts, all of them riding upon horses, a great company … [that] shalt come up against my people of Israel, as a cloud to cover the land” (Ezekiel 38:15-16). The threat of an onslaught by Satan’s soldiers only strengthened the story of Prestor John, who, in his letter, vowed to “everywhere protect the Christians” with an army of “ten thousand mounted soldiers and one hundred thousand infantrymen.”

Kings sent ambassadors into these unknown, yet mapped, lands in search of the great monarch. Priests and popes sent missionaries. At first Prestor John’s kingdom was thought to be in India, and maps of India cropped up all over Europe. In 1245 the Franciscan monk John of Plam Carpini traveled across Poland, Russia, and into Central Asia looking for India. After riding by donkey for over 100 days, Friar John arrived in the land of the Mongols and Genghis Khan. It was reported back that it was from there that the armies of Gog and Magog would be unleashed. But nowhere in that vast land was Prestor John to be found. (Starting some years later, the Mongols sacked Baghdad.)

Soon the search spread into the Near East. By the 14th century, when the Near East and India did not prove to hold the magic and wealth by now described on many travel maps, mapmakers too reluctant to discard the legend began to draw Prestor John’s kingdom in Abyssinia, now modern day Ethiopia. Once the new maps began to circulate, many envoys deep into Africa followed.

Countless crusades and exploratory excursions into the Far East, India, and Africa did not turn up the mystic Christian monarch. However, they did establish trading routines for new goods, and for the development of cartography the crusades provided a better understanding of the geography outside of Europe. And thus the isolation of medieval Europe came to an end. As economic and civil sectors boomed, the once mighty alliance that was to be made with Prestor John against the armies of Gog and Magog, and the maps depicting his kidgdom, faded into the recesses of memory.

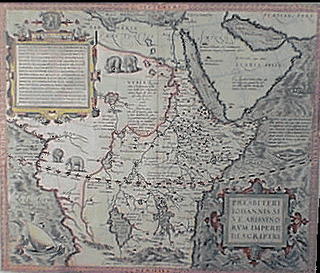

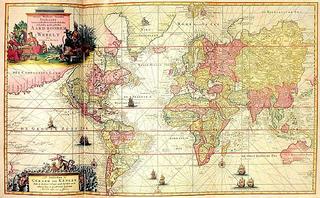

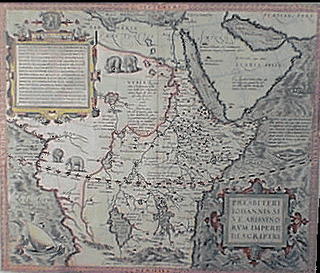

The most interesting characteristic displayed by this cartographical example is the general willingness of mapmakers to render parts of the world for which they had no geographical information. What they did know for certain about these places they mapped with some accuracy and attention. For example, a comparison of Ortelius’ map of Prestor John’s kingdom (above) to a contemporary map of central Africa shows that a lot of geographical information about Africa’s coastline was known at that time. However, what was not known was the deep interior of the continent, and that was ignored or completely fabricated. In thia unknown realm of Prestor John of central Africa, emblems of townships and holdings dot the map. Rivers and lakes are populated by these townships, supposedly a part of the kingdom. Areas not well known andnot considered a part of the kingdom were left plank or covered with signage (for example, from northwest to central western Africa). Southern Africa, being almost completely unexplored at the time by Europeans, was often left off maps completely.

Maps of Prestor John’s world were created for many reasons, some of which included mythical stories, religions, and political and economic goals. Such readiness to fabricate the world, or to replace a lack of knowledge about the world with inspired knowledge, under these kinds of social forces may be found on maps dating back the 6th century BCE. And within this we find one of the circular functions of maps: that people influence what maps represent in order to influence what people do.

PART TWO - Believing is Seeing

In 499-494 BCE an attempt was made to gain support for the Ionian Revolt against the Persians. According to the Greek historian Herodotus, a Greek by the name of Aristogoras of Miletus, the leader of the Ionian revolt, traveled to Sparta to win over the help of its dominant military power. Aristagorias’ tool of persuasion was a map.

The map was that of the known world at the time. It showed “all the seas and rivers”. It was a bronze tablet by Hecataeus. In the throne room of Cleomenes, Aristagoras made an appeal to the Spartan leader’s greed by pointing to all the lands and riches on the map which could be his if only he committed his arms to the revolt. As Aristagoras spoke, he pointed on the map of the world.

“Cleomenes, be not amazed at the eagerness of my coming here. The circumstances are these: that the children of the Ionians should be slaves instead of free men is the greatest of reproaches to ourselves, and, of all the rest of men, especially of you, inasmuch as you are the leader of Greece … What is more, these men [Persians] who live on that continent have an abundance of good things such as not all other men together have—beginning with gold, and then silver, and bronze, and dyed raiment, and beast of burden, and slaves. You may have of these all your heart’s desire. They live, too, next to one another, as I can show you [on the map]: here are the Lydians, right next to the Ionians, living in a fertile land, and they have much silver among them.”

“Cleomenes, be not amazed at the eagerness of my coming here. The circumstances are these: that the children of the Ionians should be slaves instead of free men is the greatest of reproaches to ourselves, and, of all the rest of men, especially of you, inasmuch as you are the leader of Greece … What is more, these men [Persians] who live on that continent have an abundance of good things such as not all other men together have—beginning with gold, and then silver, and bronze, and dyed raiment, and beast of burden, and slaves. You may have of these all your heart’s desire. They live, too, next to one another, as I can show you [on the map]: here are the Lydians, right next to the Ionians, living in a fertile land, and they have much silver among them.”

Once the lands of the Lydian, which bordered Greece, were “shown” as being wealthy, he pointed farther east, and spoke of other riches.

“And here, next to the Lydian,” said Aristagoars, “are the Phrygians, to the east, with more flocks than any people on earth that I know and with greater crops. Next to the Phyrgians are the Cappadocians, whom we call Syrians. On their borders are the Cilicians, whose land comes down to the sea right here, where the island of Cyprus lies. Fifty talents are what they contribute to the Great King yearly. Next [to] the Cilicians are the Armenians, here—they, too, are rich in herds—and next [to] the Armenians are the Matieni, who live in this country. Next [to] them is the Cissian land, and in it, by this river, the Choapers, in Susa, where the Great King has his lodging and where his treasure houses are. Capture that city and you may well boast that you rival Zeus in wealth.”

Enticed, Cleomenes inquired, smartly, “how many days journey it was from the Ionian sea to where the Great King was.” Here, Herodotus implies that up to his point Aristagoras’ claims about the mapped lands were fraudulent, for “In everything else Aristagoras was very clever and had tricked Cleomenes successfully, but here he tripped up.” In answering the questions of distance, Aristagoras told the truth. When Cleomanese heard that the journey would take at least three months, he refused to commit Spartan soldiers to such a conquest.

No early world maps from Greece have survived, but the story told by Herodotus suggests several points of interests. First, a map is an effective tool for categorizing objects (lands, people, treasures) into separate domains. The Lydians live here, the Phrygians there, and so on. Respectively, with the Lydians are fertile lands and silver; the Phrygians hold great flocks and crops; there are more riches elsewhere. In the act of looking at maps, one is better able to make a correlation between objects and the ideas, desires, processes, or goals towards those objects through the spatial relationships that maps construct.

Second, as a representation of what is not otherwise available to the viewer (such as future goals or possessions), maps can be misleading or even fully deceptive in what they show. In the represenation of objects or goals in written or iconographic form, we tend to give those representations more turth than actually exsist in reality. This is also illustrated in the first cartographic example by Ortelius. Where as the map described by Aristagoras was used to deceive for a purpose, maps of Prestor John’s kingdom were not intended to deceive, but render real what was imagined. Both kinds of maps were meant to influence the people who viewed them, however.

Third, the concept of a map of the world drawn to scale was unfamiliar in ancient times. An awareness of the relationship between spatial distance and time of travel was not easily conciliated into a reality. Rather, an awareness of spatial arrangement of relatedness seems more fundamental than that of time, even today. With Aristagoras’ map, Cleomenes is better able to view the spatial relationship between his kingdom and that of the Great King in Susa, but not the amount of time it would take to travel there. This is a charcateristic of human temporal perception today as well.

And forth, as an extension of the last, the reason for the use of mapping as a metaphor for knowing or communicating becomes clear: the concept of spatial relatedness is a quality without which it is difficult for the human mind to apprehend objects of knowledge. Whether one is trying to comprehend something unknown or trying to make unknown things a reality by using maps to illustrate them, in both of the above examples, the human mind endeavors to spatially place things into a relationship to itself as a means of understanding.

The characteristics outlined above are not conclusive, nor are they exclusive qualities of maps. The characteristics may be found in both examples. They are in fact true of all maps from ancient times to present day cartography (think of political maps, for the most transparent example).

“If anyone considers incredible the unheard-of things I have set down here, let him do homage to the secrets of nature, rather than consult his intellect. For nature conceives of innumerable things, of which those know to us are fewer than those not known, and this is so because nature exceeds understanding.” — Fra Mauro, medieval mapmaker

1 As quoted from a translation of The realm of Prestor John by Silverberg.

Downs © Copyright 2005

Related Post: Jan Vameer's The Art of Painting

I love maps. I am interested in them because they embody many of the things I like. Maps are cultural artifacts comparable to diaries, art objects, literature, or musical instruments. Almost every culture had developed maps, but they did it with enormously varying degrees of sophistication. The origin of maps seems instinctive, in that they are products both of the intellect and the imagination confronting problems in reality. That is, in the quest to describe reality, maps tell stories. They help construct a history in which they are a part. I like all of these things, especially stories.

I love maps. I am interested in them because they embody many of the things I like. Maps are cultural artifacts comparable to diaries, art objects, literature, or musical instruments. Almost every culture had developed maps, but they did it with enormously varying degrees of sophistication. The origin of maps seems instinctive, in that they are products both of the intellect and the imagination confronting problems in reality. That is, in the quest to describe reality, maps tell stories. They help construct a history in which they are a part. I like all of these things, especially stories.It is self-evident that the only true and accurate map of the world is a three-dimensional one. Yet, mapmakers have persistently striven to re-create the world on paper. Why? Is it simply because of the portability of a roll of parchment or vellum? Or, is it also the desire to see an image of the earth focused before us, clear, self-contained, comprehensible, and masterable? The paradox of this question is distilled within the cartographic language itself. The task, then, is to describe and interpret that language.

This essay explores the ontological nature of maps in two short parts. Part One, Believing is Seeing, focuses a medieval example of how people influence what maps show. In Part Two, Seeing is Believing, a map described by Herodotus from ancient Greek history shows how iconography can influence the behavior of people. In both cases, we see that maps help to construct a history, serve our interests, render visible that which is invisible, and interestingly, maps lie to us.

PART ONE - Believing is Seeing

The legend of Prestor John, a powerful Christian priest-king of unimaginable wealth and power, began in the 1030's, just before the start of the Great Crusades. This timing is not a coincidence. Maps that showed the kingdom of Prestor John contributed to the compulsory drive of the Crusades. And by the 12th century such maps clearly show a fictitious empire describe as belonging to Prestor John. These maps, however, show lands that had not yet been explored by western cartographers. They were, in fact, often completely imaginary.

In a lengthy letter supposedly written by the great monarch himself and sent to Emperor Manuel Commenus of Byzantine, Prestor John says, “…believe without doubting that I, Presbyter Ioannes, who reign[s] supreme, exceed[s] in riches, virtue, and power [over] all creatures who dwell under heaven … am a devout Christian and everywhere protect the Christians of our empire.”

The empire of Prestor John was a wondrous place which stretched from “the valley of deserted Babylon close by the Tower of Babel” to include “the Three Indias”. “Honey flows in our land, and milk everywhere abounds … In one of our territories no poison can do harm.” The river Physon, which “emerges[s] from Paradise”, is pebbled with diamonds, emeralds, and “many other precious stones.” There is even “a sandy sea without water. For the sand moves and swells into waves like the sea and is never still.” 1

To the medieval mind such a Christian ruler of immense riches and power would have made an ideal ally. For they feared the armies of Gog and Magog “shalt come from thy place out of the north parts, all of them riding upon horses, a great company … [that] shalt come up against my people of Israel, as a cloud to cover the land” (Ezekiel 38:15-16). The threat of an onslaught by Satan’s soldiers only strengthened the story of Prestor John, who, in his letter, vowed to “everywhere protect the Christians” with an army of “ten thousand mounted soldiers and one hundred thousand infantrymen.”

Kings sent ambassadors into these unknown, yet mapped, lands in search of the great monarch. Priests and popes sent missionaries. At first Prestor John’s kingdom was thought to be in India, and maps of India cropped up all over Europe. In 1245 the Franciscan monk John of Plam Carpini traveled across Poland, Russia, and into Central Asia looking for India. After riding by donkey for over 100 days, Friar John arrived in the land of the Mongols and Genghis Khan. It was reported back that it was from there that the armies of Gog and Magog would be unleashed. But nowhere in that vast land was Prestor John to be found. (Starting some years later, the Mongols sacked Baghdad.)

Soon the search spread into the Near East. By the 14th century, when the Near East and India did not prove to hold the magic and wealth by now described on many travel maps, mapmakers too reluctant to discard the legend began to draw Prestor John’s kingdom in Abyssinia, now modern day Ethiopia. Once the new maps began to circulate, many envoys deep into Africa followed.

Countless crusades and exploratory excursions into the Far East, India, and Africa did not turn up the mystic Christian monarch. However, they did establish trading routines for new goods, and for the development of cartography the crusades provided a better understanding of the geography outside of Europe. And thus the isolation of medieval Europe came to an end. As economic and civil sectors boomed, the once mighty alliance that was to be made with Prestor John against the armies of Gog and Magog, and the maps depicting his kidgdom, faded into the recesses of memory.

The most interesting characteristic displayed by this cartographical example is the general willingness of mapmakers to render parts of the world for which they had no geographical information. What they did know for certain about these places they mapped with some accuracy and attention. For example, a comparison of Ortelius’ map of Prestor John’s kingdom (above) to a contemporary map of central Africa shows that a lot of geographical information about Africa’s coastline was known at that time. However, what was not known was the deep interior of the continent, and that was ignored or completely fabricated. In thia unknown realm of Prestor John of central Africa, emblems of townships and holdings dot the map. Rivers and lakes are populated by these townships, supposedly a part of the kingdom. Areas not well known andnot considered a part of the kingdom were left plank or covered with signage (for example, from northwest to central western Africa). Southern Africa, being almost completely unexplored at the time by Europeans, was often left off maps completely.

Maps of Prestor John’s world were created for many reasons, some of which included mythical stories, religions, and political and economic goals. Such readiness to fabricate the world, or to replace a lack of knowledge about the world with inspired knowledge, under these kinds of social forces may be found on maps dating back the 6th century BCE. And within this we find one of the circular functions of maps: that people influence what maps represent in order to influence what people do.

PART TWO - Believing is Seeing

In 499-494 BCE an attempt was made to gain support for the Ionian Revolt against the Persians. According to the Greek historian Herodotus, a Greek by the name of Aristogoras of Miletus, the leader of the Ionian revolt, traveled to Sparta to win over the help of its dominant military power. Aristagorias’ tool of persuasion was a map.

The map was that of the known world at the time. It showed “all the seas and rivers”. It was a bronze tablet by Hecataeus. In the throne room of Cleomenes, Aristagoras made an appeal to the Spartan leader’s greed by pointing to all the lands and riches on the map which could be his if only he committed his arms to the revolt. As Aristagoras spoke, he pointed on the map of the world.

“Cleomenes, be not amazed at the eagerness of my coming here. The circumstances are these: that the children of the Ionians should be slaves instead of free men is the greatest of reproaches to ourselves, and, of all the rest of men, especially of you, inasmuch as you are the leader of Greece … What is more, these men [Persians] who live on that continent have an abundance of good things such as not all other men together have—beginning with gold, and then silver, and bronze, and dyed raiment, and beast of burden, and slaves. You may have of these all your heart’s desire. They live, too, next to one another, as I can show you [on the map]: here are the Lydians, right next to the Ionians, living in a fertile land, and they have much silver among them.”

“Cleomenes, be not amazed at the eagerness of my coming here. The circumstances are these: that the children of the Ionians should be slaves instead of free men is the greatest of reproaches to ourselves, and, of all the rest of men, especially of you, inasmuch as you are the leader of Greece … What is more, these men [Persians] who live on that continent have an abundance of good things such as not all other men together have—beginning with gold, and then silver, and bronze, and dyed raiment, and beast of burden, and slaves. You may have of these all your heart’s desire. They live, too, next to one another, as I can show you [on the map]: here are the Lydians, right next to the Ionians, living in a fertile land, and they have much silver among them.”Once the lands of the Lydian, which bordered Greece, were “shown” as being wealthy, he pointed farther east, and spoke of other riches.

“And here, next to the Lydian,” said Aristagoars, “are the Phrygians, to the east, with more flocks than any people on earth that I know and with greater crops. Next to the Phyrgians are the Cappadocians, whom we call Syrians. On their borders are the Cilicians, whose land comes down to the sea right here, where the island of Cyprus lies. Fifty talents are what they contribute to the Great King yearly. Next [to] the Cilicians are the Armenians, here—they, too, are rich in herds—and next [to] the Armenians are the Matieni, who live in this country. Next [to] them is the Cissian land, and in it, by this river, the Choapers, in Susa, where the Great King has his lodging and where his treasure houses are. Capture that city and you may well boast that you rival Zeus in wealth.”

Enticed, Cleomenes inquired, smartly, “how many days journey it was from the Ionian sea to where the Great King was.” Here, Herodotus implies that up to his point Aristagoras’ claims about the mapped lands were fraudulent, for “In everything else Aristagoras was very clever and had tricked Cleomenes successfully, but here he tripped up.” In answering the questions of distance, Aristagoras told the truth. When Cleomanese heard that the journey would take at least three months, he refused to commit Spartan soldiers to such a conquest.

No early world maps from Greece have survived, but the story told by Herodotus suggests several points of interests. First, a map is an effective tool for categorizing objects (lands, people, treasures) into separate domains. The Lydians live here, the Phrygians there, and so on. Respectively, with the Lydians are fertile lands and silver; the Phrygians hold great flocks and crops; there are more riches elsewhere. In the act of looking at maps, one is better able to make a correlation between objects and the ideas, desires, processes, or goals towards those objects through the spatial relationships that maps construct.

Second, as a representation of what is not otherwise available to the viewer (such as future goals or possessions), maps can be misleading or even fully deceptive in what they show. In the represenation of objects or goals in written or iconographic form, we tend to give those representations more turth than actually exsist in reality. This is also illustrated in the first cartographic example by Ortelius. Where as the map described by Aristagoras was used to deceive for a purpose, maps of Prestor John’s kingdom were not intended to deceive, but render real what was imagined. Both kinds of maps were meant to influence the people who viewed them, however.

Third, the concept of a map of the world drawn to scale was unfamiliar in ancient times. An awareness of the relationship between spatial distance and time of travel was not easily conciliated into a reality. Rather, an awareness of spatial arrangement of relatedness seems more fundamental than that of time, even today. With Aristagoras’ map, Cleomenes is better able to view the spatial relationship between his kingdom and that of the Great King in Susa, but not the amount of time it would take to travel there. This is a charcateristic of human temporal perception today as well.

And forth, as an extension of the last, the reason for the use of mapping as a metaphor for knowing or communicating becomes clear: the concept of spatial relatedness is a quality without which it is difficult for the human mind to apprehend objects of knowledge. Whether one is trying to comprehend something unknown or trying to make unknown things a reality by using maps to illustrate them, in both of the above examples, the human mind endeavors to spatially place things into a relationship to itself as a means of understanding.

The characteristics outlined above are not conclusive, nor are they exclusive qualities of maps. The characteristics may be found in both examples. They are in fact true of all maps from ancient times to present day cartography (think of political maps, for the most transparent example).

“If anyone considers incredible the unheard-of things I have set down here, let him do homage to the secrets of nature, rather than consult his intellect. For nature conceives of innumerable things, of which those know to us are fewer than those not known, and this is so because nature exceeds understanding.” — Fra Mauro, medieval mapmaker

1 As quoted from a translation of The realm of Prestor John by Silverberg.

Downs © Copyright 2005

Related Post: Jan Vameer's The Art of Painting

Monday, October 17, 2005

Wednesday, October 05, 2005

Saturday, October 01, 2005

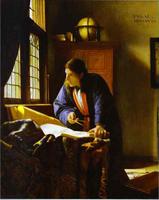

Jan Vermeer’s The Art of Painting

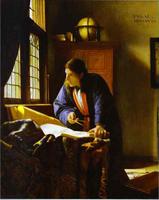

In his allegorical work, The Art of Painting, Jan Vermeer gives the map of the Netherlands a central place on the canvas. The figure of a young woman stands just before it, draped in blue and holding a trumpet and a book. She poses, taking on the role of representing History. The image of History, an event that necessarily calls for interpretation, is thus juxtaposed with the map of a history of the Netherlands. The map, which we see is like a painting, is also a version of history. It records the Netherlands as transformed by the towns, bridges and towers of human endeavor, as well as by the craft of mapmaking. This transformation is situated behind History, and she, interestingly, has her back to it, not because she disregards it, but because she has no part in what or how history is represented. Instead, she faces us and the artist.

In his allegorical work, The Art of Painting, Jan Vermeer gives the map of the Netherlands a central place on the canvas. The figure of a young woman stands just before it, draped in blue and holding a trumpet and a book. She poses, taking on the role of representing History. The image of History, an event that necessarily calls for interpretation, is thus juxtaposed with the map of a history of the Netherlands. The map, which we see is like a painting, is also a version of history. It records the Netherlands as transformed by the towns, bridges and towers of human endeavor, as well as by the craft of mapmaking. This transformation is situated behind History, and she, interestingly, has her back to it, not because she disregards it, but because she has no part in what or how history is represented. Instead, she faces us and the artist. We see now that the image is laden with both the events that the discourse of history wishes to describe and the function of description itself.

We see now that the image is laden with both the events that the discourse of history wishes to describe and the function of description itself. In contrast, the artist sits with his back to us, anonymous and faceless. His eyes are buried and hidden by his task. Who is this person who is recording History? One cannot discern to where his attention is directed: is it the model or the canvas—History or representing History? He is lost within the very world which he represents, simultaneously between History and recording it on his canvas.

In contrast, the artist sits with his back to us, anonymous and faceless. His eyes are buried and hidden by his task. Who is this person who is recording History? One cannot discern to where his attention is directed: is it the model or the canvas—History or representing History? He is lost within the very world which he represents, simultaneously between History and recording it on his canvas.Similarly, we, the viewers, are left suspended in a dim light. We are pushed back and away from the world being represented by a drapery that hangs between the outside world and that of the painting. We repeat the task of the painter, for we are removed from our subjects and we are now confronted with the task of interpreting them. So then, are we removed from the act of representing history as well, like the painter? Is not to look at a painting the act of interpretation of a history, its history?

Together, the woman as History with the map as historical emblem and the painter, set forth the multi-faced cycles of the image. First, the art of the painting contains within itself the impulse to map or describe, and visa-versa. Second, observation is shown to be inseparable from the act of representing, or the interpretation and the recording of history. And third, the events of history themselves are impossible to encounter or fully grasp.

Downs - Copyright © 2005

Related Post: The Nature of Maps